Going to The Head

In naval parlance, “going to the head” has always meant something unglamorous: a visit to the toilet. The phrase goes back to the days of tall ships and square riggers, when the sailors’ privy was located at the bow—the “head”—of the vessel, where wind and waves could carry the smell away.

But if you lived at the top end of Lake Wakatipu before 1980—on one of the sheep stations strung along the western shore, like Dart Valley, Mount Creighton, Paradise, or Rees Valley—“going to the Head” meant something entirely different. It meant going to Glenorchy, the village at the head of the lake. And nothing symbolised that more than the TSS Earnslaw.

A grand old lady of steam, the Earnslaw was more than a boat. She was a lifeline. A floating post office. A general carrier. A ferry. A wool boat. A people mover. A link between worlds. In the age before sealed roads and utes on every corner, everything and everyone on Lake Wakatipu moved by water.

She was also regular. The Earnslaw kept a tight schedule: Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays were Boat Days, marked in pencil on every kitchen calendar from Kinloch to the Greenstone.

On Boat Day, the mail came. The Green Bag brought the newspapers, letters, and the mysterious parcel from Christchurch that turned out to be a part for the shearing plant, lessons from the Correspondence School, or a box of lamb teats. The shearers arrived too: ferried up the lake with their handpieces and bedrolls, sometimes still hungover from Queenstown the night before. And when the job was done, the wool went back down the same way it came: by the boat, bale after bale lashed and stacked and swung aboard by crane.

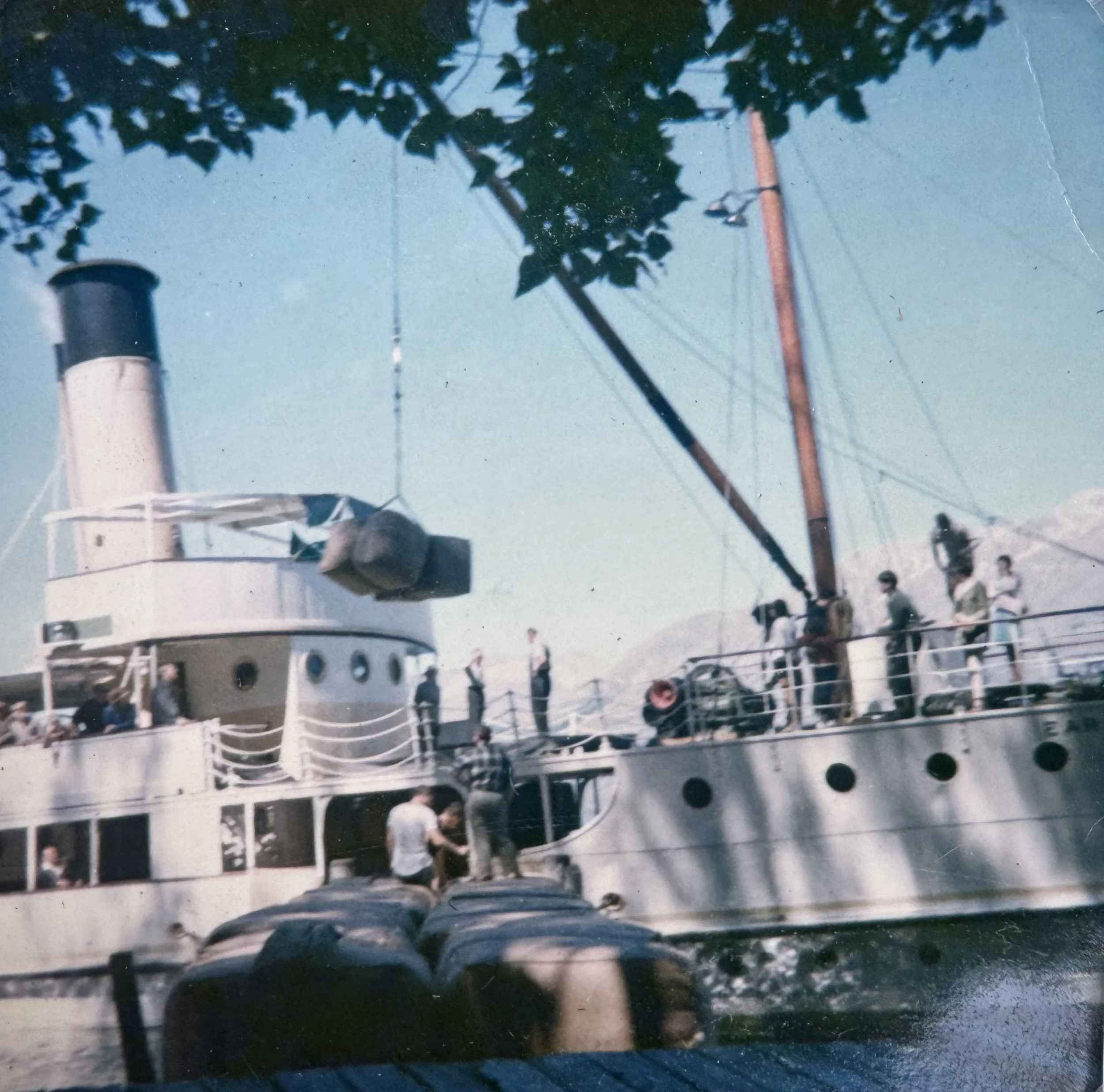

There’s a photograph from Mount Creighton Station in 1967. Bales of wool are being loaded onto the Earnslaw from the end of the station jetty. A man on the wharf signals up to the winch. The crane takes the strain. The bale lifts clean off the deck and swings slowly over the water like a pendulum.

But it's not just wool in the frame. In another photograph, sitting atop a row of tightly-packed bales, looking small beneath the vast sweep of lake and sky, are a woman and a baby. My wife’s brother, Ivan, just a toddler at the time, and her mother, Helen. They're relaxed, unhurried. As if it’s the most normal thing in the world to perch on a season’s clip, high above the water, while the Earnslaw takes on her load.

And it was normal. From Plunket nurses to bulls, from deckhands to dead bodies, from crates of eggs to cases of explosives: everything and everyone made that lake crossing eventually. Glenorchy wasn’t just “at the Head.” It was the Head. The place where everything began and everything returned.

Loading the clip at Mount Creighton jetty, 1967.

Wool from the stations was trucked or sledged down to the landing. A Bedford truck driven by my wife’s grandfather, Charlie Hume, or someone like him, would rumble onto the jetty and drop its tailgate. Bales were rolled off and down, ready for the hook. On Thursdays, lambs were loaded too—up to fifteen hundred at a time—bound for the saleyards at Lumsden or Gore.

And then she’d go. The Earnslaw. Her whistle echoing off the hillsides, her steam engine churning the propeller steadily through the green-blue water, a white wake trailing behind her like a ribbon. You could track her progress from the ridgeline above: just a speck of white hull and curl of black smoke slipping down past Pig Island, toward Kingston and the wider world.

The TSS Earnslaw passing the front gate of Mount Creighton Station, 1963.

Today, the Earnslaw is mostly a tourist steamer. She carries cameras and coffee, not crutchers or cull lambs. But for those who lived by the lake—who loaded her deck with bales and memories—she’s still something else. A working vessel. A heartbeat. A symbol of what it meant to live at the end of the road, in a place where the only way out was by water.

And even now, if you hear someone say they're “going to the Head,” you can smile, knowing it means more than a pit stop. It means Glenorchy. It means the lake. It means wool on the wharf, kids on the bales, and the steady chuff of steam as the boat pulls away.

Ivan Key and Helen Key (neé Hume) on the jetty at Mount Creighton, 1967.

The Church of the Good Shepherd

The Church of the Good Shepherd sits amid lupins and tussocks, on the southern shore of Lake Tekapo, with its back to the lake and its face to the Southern Alps.

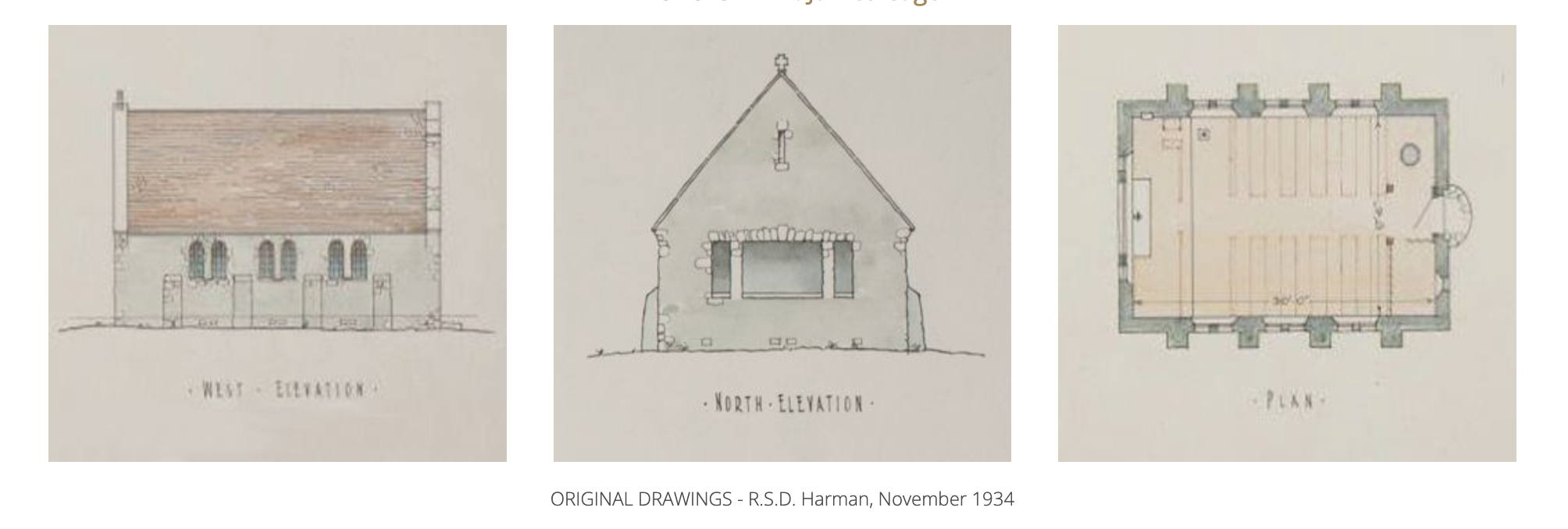

Built in 1935, the church owes its design to drawings by the artist Esther Hope of Grampians Station. These days, the church is a postcard fixture, a must-stop for tourists that has graced social media platforms from Beijing to Walton-on-Thames.

One of the church’s original design remits was that it should not disturb the ground upon which it sits in any way. The brief given to its builders was that no plants or stones were to be moved or removed from the site, and that the stone for its walls was to be sourced within a five-mile radius.

And that's where Doug Rodman enters the story. He was the man who built the Church of the Good Shepherd. Doug was a friend of my father's. The house where he lived with his wife, Peg, was on McDonald Street, overlooking the river, and my brother and I would sometimes accompany our father when he visited Doug’s house.

I was fascinated by his basement. The space smelled of old wood, Scandinavian oils, sherry-soaked cigarette smoke (Doug was a confirmed alcoholic), and the sharp iron tang of auger bits biting into timber. It was a place of tools and patience: curled wood shavings, handsaws, jack planes, sash cramps, chisels. I still have the wooden chisel mallet he gave me, and the jack plane that I used, among other jobs, when I worked as a carpenter on the restoration of the old boarding house at Rangi Ruru in Christchurch. Tools are like mementos that pass from hand to hand, their stories intertwining with those of the people who work with them. The wooden mallet Doug gave me, I used to make imitation reindeer hoofprints on our lawn every Christmas Eve, a ruse that convinced our daughters of Santa's existence for years.

Doug Rodman was an old-school craftsman, even if his reputation for drink was as firm as his grip on a square. He and his cobber, Les Loomes, had raised the walls of the church beside the lake, laying the stones by hand, mortising the joints, cutting the bird’s-mouth seats of the rafters, splitting and fitting the timber roof shingles, and installing the joinery. And in doing so, he had become part of something much larger than himself.

Lake Tekapo and the Two Thumb Range

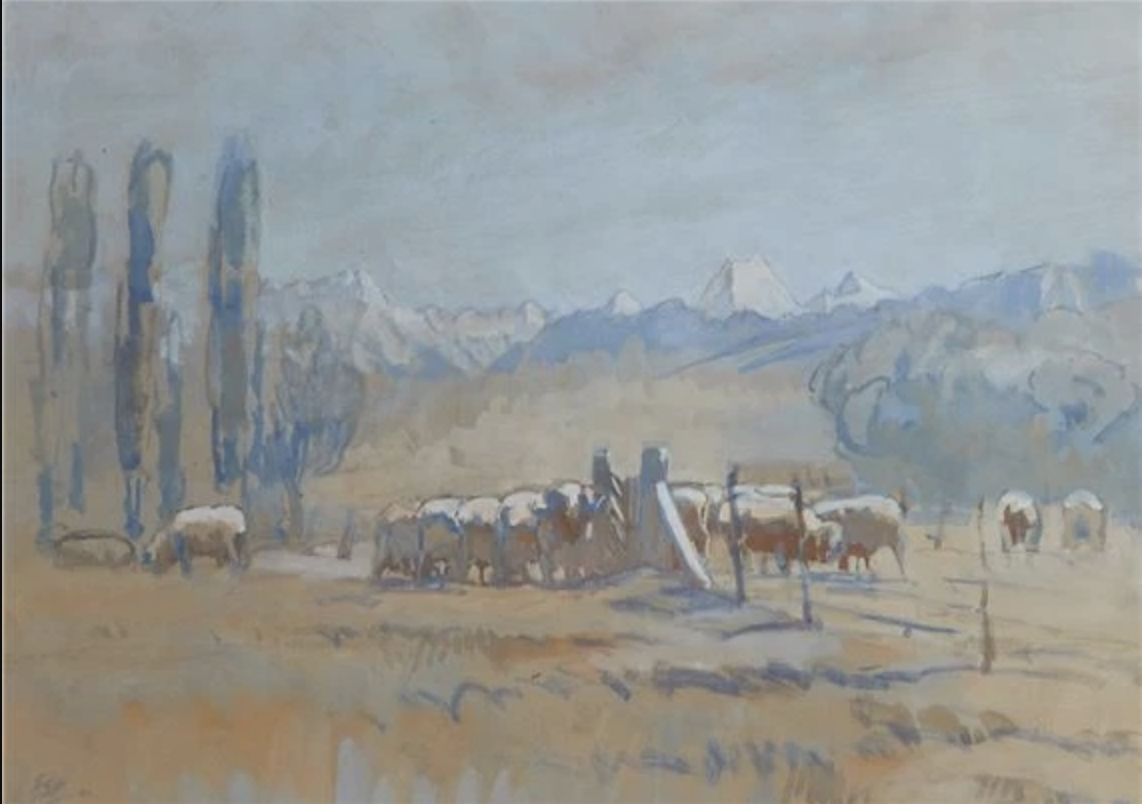

Esther Hope, the artist who produced the conceptual drawings of the church, was born in 1885 in Woodbury, just down the street from another church, St Thomas', where my wife and I were married. Esther studied art in London at the Slade School of Fine Art and the Chelsea College of Arts. After completing her education, she spent several years perfecting her craft in Europe. She was in Brittany when World War I broke out and, upon returning to England, she worked as a truck driver and as a Voluntary Aid Detachment driver in Malta. When the war ended, Ester returned to New Zealand and married Harry Hope, the owner of Grampians.

At Grampians, Esther Hope began painting the landscapes of the Mackenzie Country: the vast sky, the long views framed by pencil-thin Lombardy poplars, the sinuous curves of the willow-lined creeks on the beige background of the basin, and the distant, glacier-encrusted line barrier of the Southern Alps. These were views that I came to know intimately: on foot, on horseback, through the windscreen of my Holden ute and in the blur of a dog’s run.

The view from Grampians, Watercolour by Esther Hope.

The same view as the watercolour above, photographed by me in December 1981.

What Esther captured in watercolour, I traced in dust and sweat and stock movement. Her brush followed the contours my boots did. The light she washed onto the page was the same light I watched falling across the hills at dusk. And in both acts—hers and mine—there was the same quiet reverence for land, weather, and the long lines that stretch across memory.

Her granddaughter, Sally, is also an artist. In November 1981, she and her husband, Nigel Buxton-Hope, came to live at Grampians for the summer. Nigel worked alongside us during the lamb-marking season that year. He was from Brixton: London-born, freshly steeped in the aftermath of the Brixton Riots, more familiar with the acrid smell of exhaust and gutters than the fresh, clear air of the South Island. We called him “The Brixton Basher”, more out of affection than mockery.

At the time, none of us really understood the political landscape he’d come from. To us, he was just another pair of hands to lift lambs and another set of stories to tell. Like his wife and his wife’s grandmother, Nigel was also an artist. He’d sketch during smoko: drawing dogs, our faces, the jagged ridgelines that framed the paddocks of The Whalesback. He moved with the grace of someone used to crowds, noise and the feel of asphalt underfoot. And yet here he was, out on the flats of the Mackenzie Basin, knee-deep in lambs, the smell of blood and steel filling the air instead of the aromas of diesel smoke, uncollected garbage, and weed.

Tailing in the Mackenzie Pass, November 1981.

In July 1882, another of Sally Hope’s ancestors, Arthur Hope, married Francis Tripp, the daughter of runholder Charles Tripp, the pioneer high country farmer and owner of Orari Gorge Station. Tripp himself had married one of the daughters of Henry John Chitty Harper, the Anglican bishop of New Zealand. In the same ceremony, another of Bishop Harper’s daughters had married my great-grandfather, Charles Robert Blakiston. That meant that Sally and I shared some family connections, with her great-grandfather and my great-grandfather being brothers-in-law.

And so it was that these strange, tenuous threads—of blood and circumstance, of tools and traditions, of wood shavings and watercolour—connected us all, with the Church of the Good Shepherd standing like a spoke in a wheel of memory, faith and place.

The Church of the Good Shepherd was designed to blend with its environment. The stonework was left rough, lichen allowed to grow, and the native vegetation untouched. It wasn’t built to stand out. It was built to belong, not just to the landscape, but to the history of the shepherd. It was intended as a memorial: to commemorate the pioneers of the Mackenzie Basin. But for me, as a young shepherd, it was something more immediate. It was a waypoint. A familiar shape on the skyline as I moved sheep through that wide, weathered country. The lake glinting beside it, the mountains behind, the dogs panting, and the wind sharp with snow. That church wasn’t just a symbol. It was part of the geography of my working life.

Back then, it wasn’t locked. There were no fences or guards. You could walk in, sit quietly, listen to the creak of timber and the hum of lake wind against the walls. The view from the altar—a wide window framing the lake and the mountains—wasn’t a metaphor. It was reality. And somehow, that made it all the more sacred.

To me, the Church of the Good Shepherd is a reminder that beauty doesn’t need polish. That faith doesn’t need grandeur. And that those who work with their hands—men like Doug Rodman—shape not just buildings, but memory.

When I think of that church now, I don’t picture the tour buses or the selfie sticks. I picture the dust on Doug’s overalls. The curl of a wood shaving. The heavy thud of a plane on totara. The way that the colours of Esther Hope’s paintings bleed into each other. And the silence inside that little chapel, where the light filters through rough glass and the land seems to hold its breath.

History, you see, is not just what is written down. It is also what is carried forward in memory, in hand tools, in sketches, in names spoken at tailing pens and around kitchen tables. It is carried in buildings and in banter, in windblown introductions, in nicknames that outlive first names, in watercolour shades on linen paper, and in the quiet, instinctive way someone rolls a cigarette or sharpens a blade.

Looking back, it’s astonishing how these threads—these echoes of those who came before—interconnect with each other, however obliquely. The church by the lake, designed by a woman born in Woodbury, not far from the church where I was married. Her granddaughter's husband, fresh from the urban unrest of London, working alongside me on the station, tailing lambs in the dust and sun. And Doug Rodman, steadying a lintel under the alpine sky, unknowingly anchoring all these lives to one rough little building that still stands.

Sheep in the Mackenzie Pass, watercolour by Esther Hope.

Footrot Flashbacks: The Shepherd’s Long Battle with Lame Sheep.

Foot rot. Even now, the words make my shoulders tense. If you've ever worked with sheep, you know the war. For me, during my years at Grampians Station, foot rot was the perennial enemy: silent, smelly, and soul-sapping. It arrived after Christmas like clockwork, and it never left quietly.

Foot rot is an infectious, highly contagious bacterial disease that affects the hooves of sheep. It thrives in damp, muddy conditions where soft hooves and bacteria make easy companions. It usually starts with Fusobacterium necrophorum, which breaks down the skin and tissue, and is followed by the more damaging Dichelobacter nodosus, which burrows deep into the hoof, causing rot between the toes, lameness, and that unmistakable stink.

Once it takes hold, it can spread through a mob like wildfire. Sheep go lame, graze less, and lose condition. And if you don’t get on top of it fast, you’ll spend the rest of the season chasing limping stragglers through the wet.

Foot trimming in the old Grampians woolshed, January 1983. L-R: N. Harraway, I. Anderson, T. Wall, V “Skippy” Gepp.

At Grampians, the annual battle against foot rot began just after New Year's and often dragged on for months. We’d set up a wooden cradle in the back of the woolshed and spend day after day tipping over ewes and wethers, trimming their hooves back to clean, even edges. Each sheep, each foot, every day.

It was mind-bendingly boring, hard, hard work: the kind that leaves a permanent ache in your back and a light dusting of PTSD in your brain. To stay sane, we played cassette tapes nonstop. For me, nothing brings it all back faster than Seven and the Ragged Tiger by Duran Duran. The opening chords of “The Reflex” and I’m there again: elbow-deep hoof trimmings, my paring shears in hand, with the sharp sting of formalin curling through the air like a chemical ghost. Even now, one whiff of it and I half expect someone to hand me a pair of shears and a list of mobs.

And yet… I reckon I could still trim a merino ewe’s hoof back to exactly the right shape, even now, more than forty years since the last time I did it at Grampians. It’s a muscle memory etched into the hands.

After the trimming came the troughing. We’d drag portable footrot baths from paddock to paddock, fill them with a cocktail of water and formalin or zinc sulphate, and run mobs through in a desperate attempt to kill the bacteria and harden their hooves. It worked. Sometimes. But foot rot is nothing if not persistent. One wet week and you were back where you started—like painting the Sydney Harbour Bridge—with paring shears, a sharp pocket knife, and swear words.

Years later, working at Wylie Valley Meats in Warminster, Wiltshire, I had a tidy little side hustle trimming feet for local farmers. I had my own pair of foot rot shears, the experience to use them properly, and a reputation that spread just enough. Hobby farmers would call me up, and I’d head out to trim a few dozen ewes for pocketfuls of pound coins. A bit of sweat, a bit of banter, and enough cash to buy beer and beans for the week.

The only good footrotting shears: long, thin, narrow blades and easy-close spring.

And it wasn’t just me. Years later, reading Shepherd Lore, I came across stories of the old Wiltshire boys and their own “receipts” for foot rot; family formulas passed down and never questioned. One old shepherd swore by a particular green dressing and a special rubber boot to keep the muck out. He had no idea what it was made of, just that it worked.

Another Wiltshire shepherd was quoted as saying: “’T’yent my religion to have lame yeows 'bout. I c’n cure 'em, but t’yent no good messin’ 'bout wi’ the yeows when the be heavy in lamb like theasums.” That makes perfect sense to me. Treat what you can, when you can, but don’t stress a ewe close to lambing just for the sake of tidy feet. Know the rhythm of the job. Timing is everything.

These days, things have improved. Better breeding, better pasture management, and better treatments. But foot rot is still out there, lurking like a bad smell in the wet corner of your memory. Despite all the science and chemicals, foot rot still recurs. The battle goes on.

The shepherd’s life is full of glory in small, quiet moments: on a ridgeline with your dogs, under the stars, during a lambing beat at sunrise. But it’s also about the drudgery, the hard yards in the yards, the weeks bent over hooves, humming Duran Duran and wondering if this will be the year it finally goes away for good. It won’t. But we’ll keep trimming. Keep troughing. Keep scanning the mob for that tell-tale hobble. Because that’s what shepherds do.

Copper Memories and Silver Plates

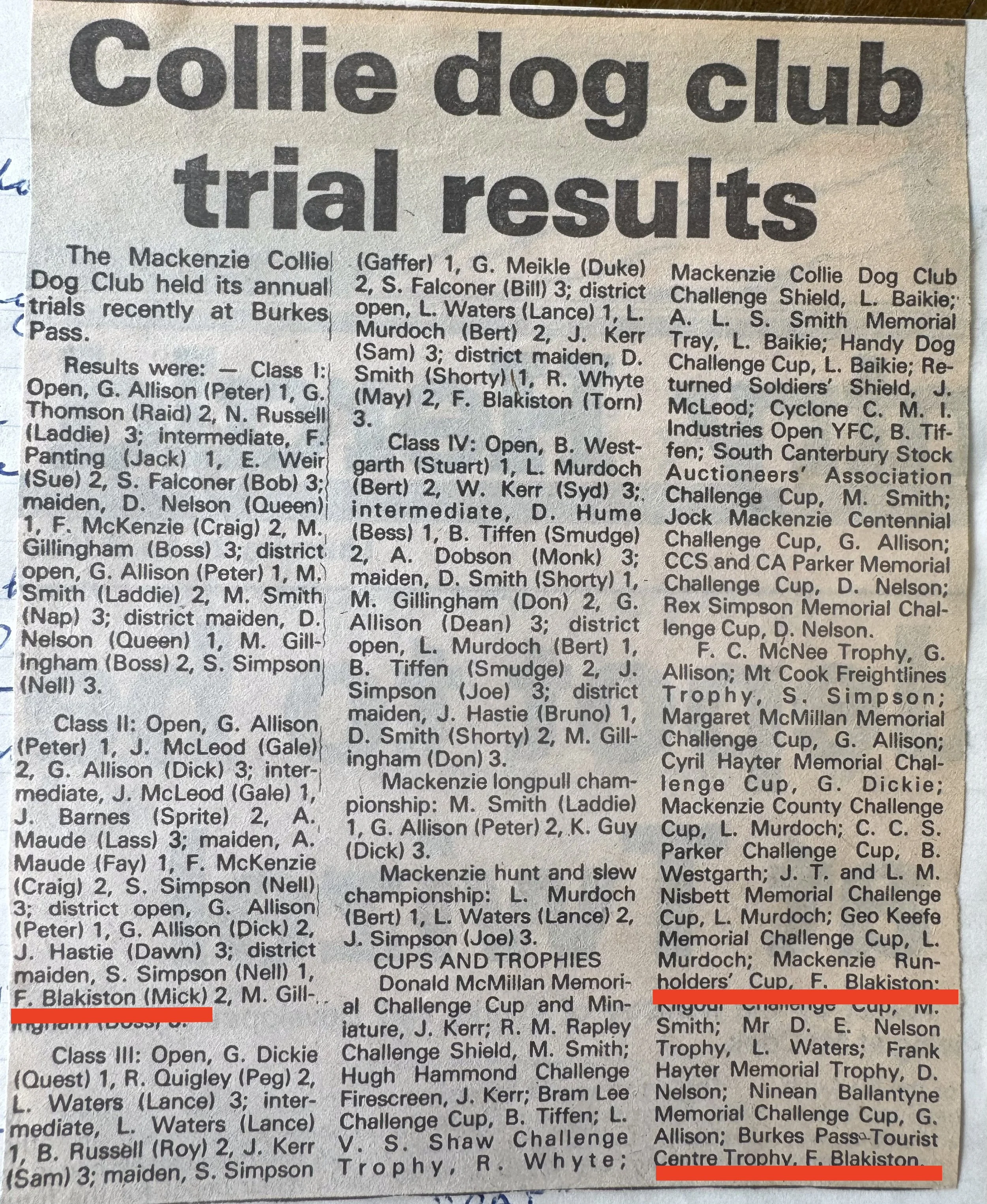

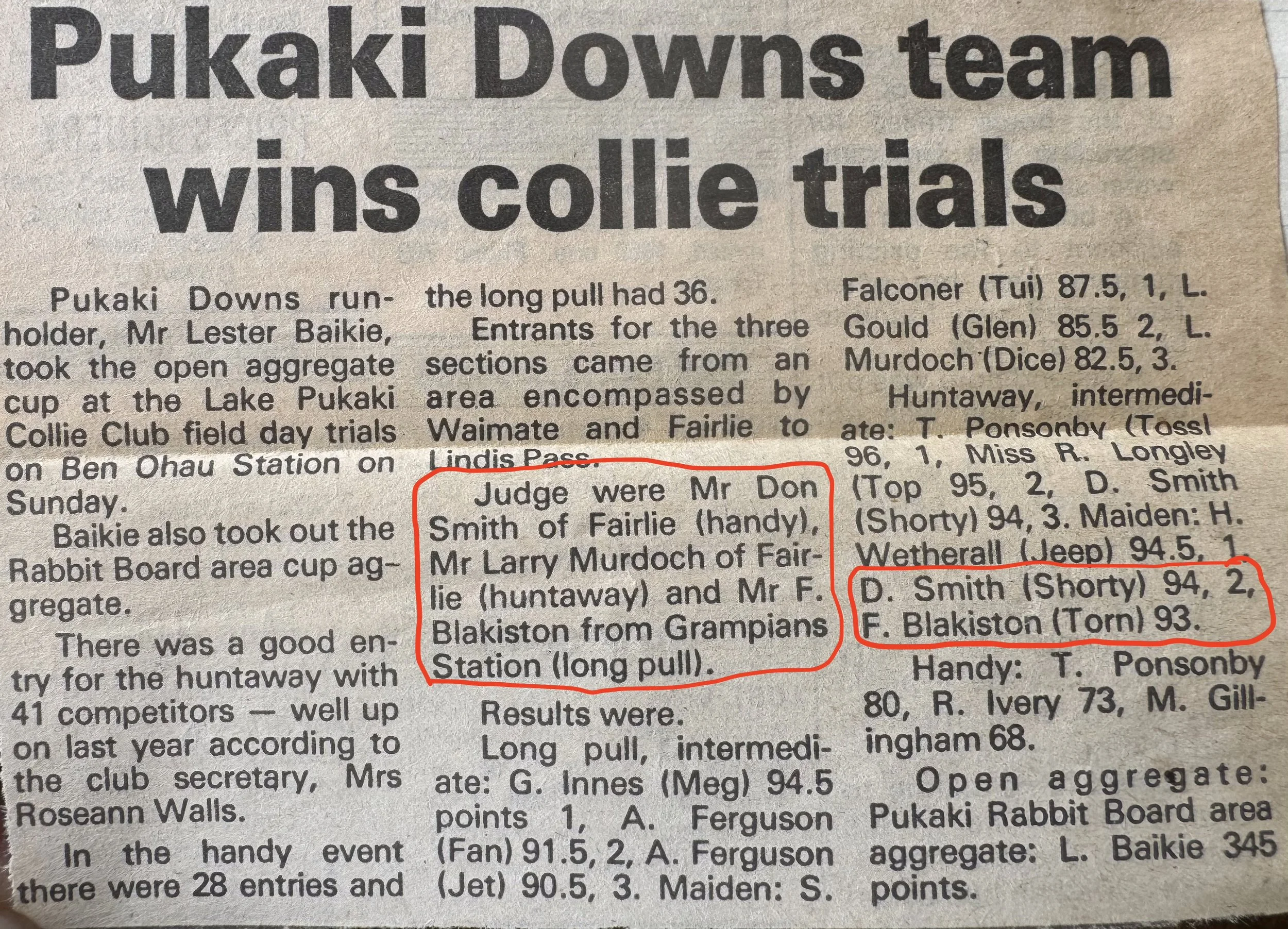

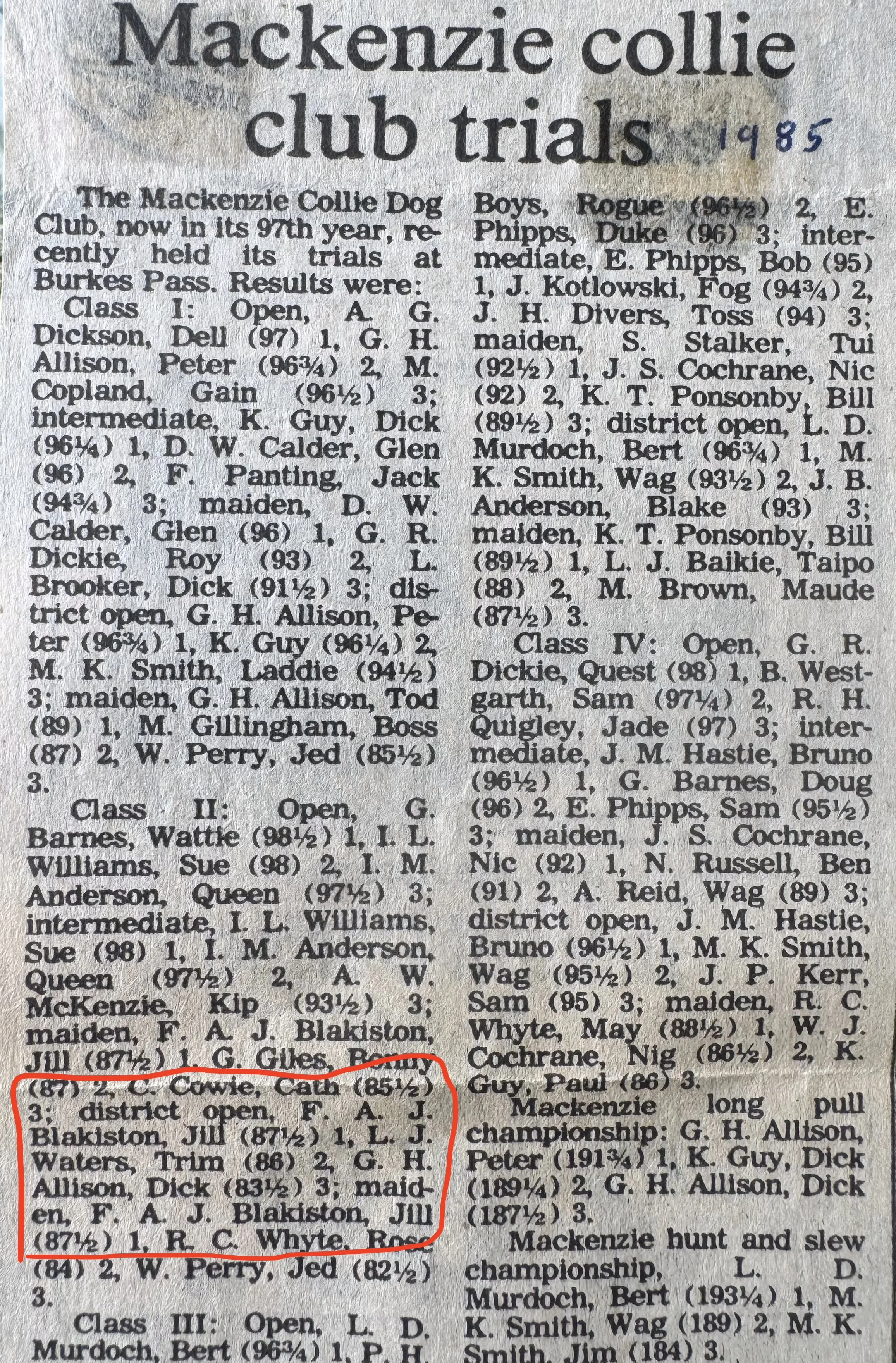

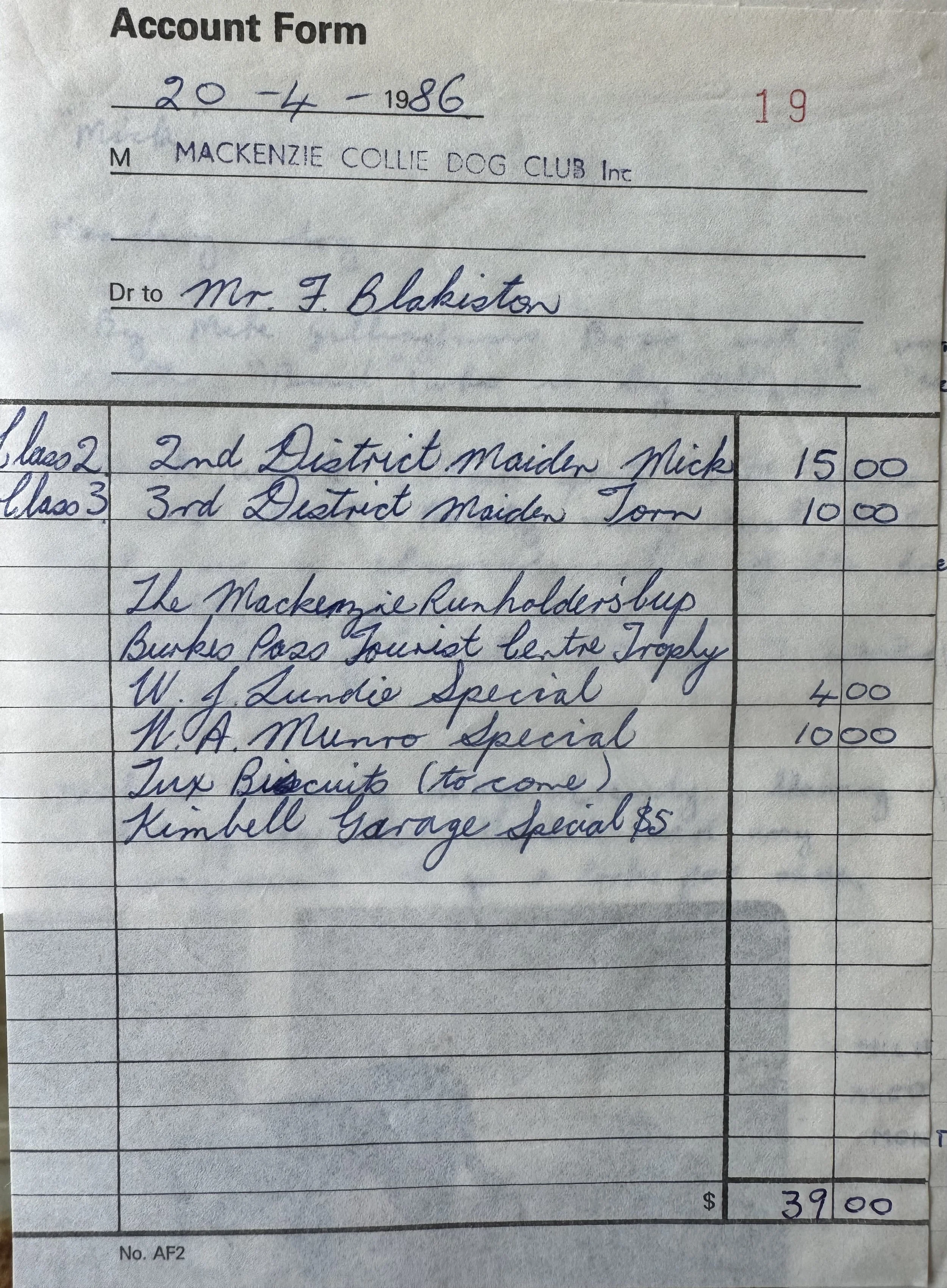

Jill and the trophies she won at the Mackenzie Collie Club Trials in 1985.

In the Kimbell Pub, on the wall beside the pool table, hang two copper plaques. Their surfaces are dark with age, polished only where fingers have traced the names. They once hung on the wall beside the bar in the Burke’s Pass Pub: before the fire, before the roof collapsed, before the only thing to make it out unscathed was the dog trial memorabilia. The exact cause of this is still a mystery. Maybe the old gods of the hill country have a soft spot for collies and triallists.

Those plaques carry history in every engraved line. They bear the names of all the shepherds who have won open titles at the Mackenzie Collie Club Trials. Names I remember: Geoff Allison, Tony Wall, Stuart Falconer, Ian Anderson, J.P. Kerr, Bruce Westgarth, Larry Murdoch. Men I worked with at Grampians, Black Forest, Dry Creek, and Blue Mountain. Men whose dogs could slide a mob through a tight gate without breaking stride. Men who drank their tea black and counted sheep in twos without blinking.

Dogs that I remember, too. Peter Kerr’s Blue was a nasty little tri-coloured brute, but he would whisk three sheep down the course in an eye-blink. Bruce Westgarth’s Stuart was a big, grinning beardie, named after another fellow whose moniker appears on the plaque. And Geoff Allison’s Ken, a world champion eye dog who could stare down the stroppiest ewe and force sheep into the pen by sheer hypnotic willpower.

Dog trials weren’t just a sport. They were a measure of a shepherd’s skill, a place where quiet men became local legends for a perfect cast, a clean lift, or a tricky pen done smooth as silk. I earned my own modest place in that lineage with Jill, my quiet-eyed heading dog. We won the plate and cup at the 1985 Burke’s Pass trials. I still have the clippings somewhere—Jill, Tornado, Mick, Bess—all mentioned in print, my name beneath theirs like a footnote.

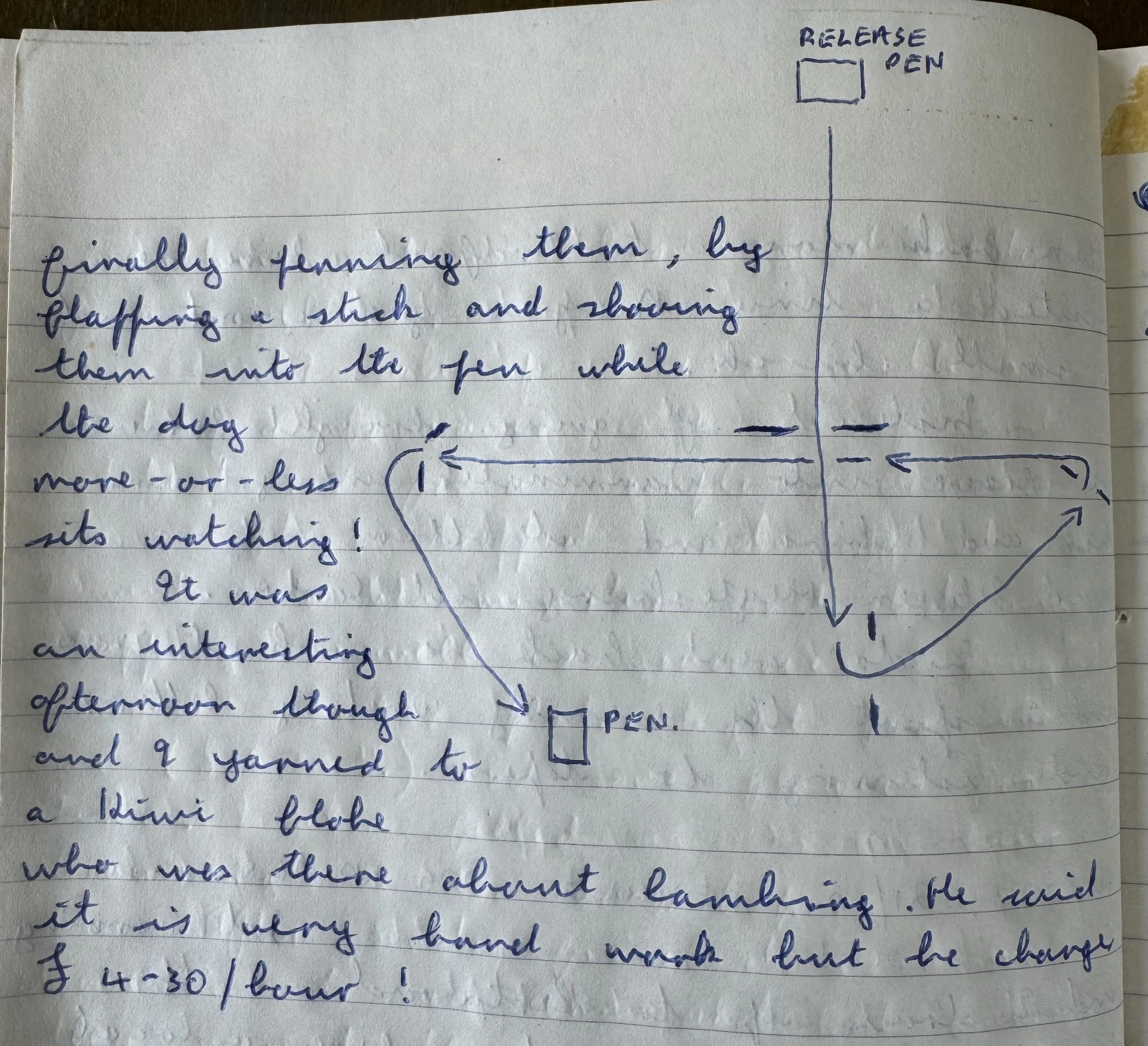

My diary entry for October 10th, 1990.

And there was the Pertwood Dog Trial in Wiltshire, 1990. It was a grey, stormy day, the kind that makes the wind howl through your bones. I drove up to the downs near Warminster, where the trial was being held in a small, wind-snatched valley. The format was simple: pull six sheep down off the hill, drive them through hurdles, then pen them with a stick-flap and a prayer while the dog sits watching.

It was different to the trials at home, but the rhythm and connection were the same. A whistle on the wind and a dog that knows what to do before the sheep do. It’s about the way a good run makes the hair stand up on your arms, and how long after you’ve left the hill, you still hear the bark, the whistle, the slow, steady heartbeat of sheep hooves on damp earth.

Dog trialling began, as most good things do, out of necessity. Long before prizes, plaques, or folding chairs in a paddock, there were just men, dogs, and sheep that needed shifting. The earliest trials didn’t have judges or scorecards—just neighbours gathered to see whose dog could work a mob cleaner, quicker, with fewer shouts and more style.

The first recorded sheepdog trial took place in Bala, North Wales, in 1873. A few Welsh farmers put up prize money and gathered on a hillside to watch dogs do what they’d been doing for centuries. Word spread. The idea caught on, and by the end of the 19th century, trials were being held across the British Isles and, soon after, in the colonies: Australia, New Zealand, and even Canada.

In New Zealand, dog trials arrived with the Scottish shepherds who brought not just their collies but a certain quiet pride in their craft. Out here, the land was wilder, the distances longer, and the weather always a character in the story. Trials became a way to hone skills, share knowledge, and—occasionally—resolve disputes without resorting to violence. They were part competition, part celebration, part confirmation that what we did on the hill mattered.

Clubs were formed. Rules refined. A points system emerged to judge not just success, but style. Trials were divided into events. Class One: the Long Pull; Class Two: the Drive and Yard; Class Three: the Straight Hunt; Class Four: the Zig-zag Hunt. The dogs had to read the sheep, the handler had to read the dogs, and the crowd sat silent, like prayers, watching it all unfold like a chess game played at speed.

By the mid-20th century, dog trials were a fixture in rural calendars. In the Mackenzie Country, they were often the only reason to shave, clean your boots, and put on a decent shirt. Crowds would gather at stations and showgrounds, camp chairs and thermoses in tow, to watch the quiet magic of a good dog at work. The real competitors weren’t just after ribbons. They were after respect; the nod from a fellow shepherd that said, “Hell of a run, mate.”

I still remember the day I won the Class Two Maiden in the 1985 Mackenzie Collie Club trials at Burke’s Pass. It was pouring with rain, and I was the last competitor of the day. Jill ran out in a perfect question mark, lifted the sheep from the hook without a halt, and brought them down the hill at a blistering pace, splashing through puddles and crashing through the matagouri.

We drove the sheep through the hurdles at full speed (I remembered to walk between them myself or else I’d be disqualified) and reached the pen with five minutes to spare. The three sheep circled the pen half a dozen times, but Jill never lost contact with them. And then, out of sheer desperation to escape Jill, the sheep dove into the pen. I closed the gate and bowed to the crowd, or what remained of it: most of the spectators had adjourned to the Burke’s Pass pub by then. But that run won me the plate that year.

And that’s the heart of it all. Those copper plaques on the pub wall, the history of the dog trials, and these small victories that live on in memory. It’s about the rhythm of a dog and a shepherd moving as one, and the stories we tell when we’re back inside, drying off by the fire, with a quart bottle of DB in your hand. In the end, once you’ve run a good dog trial, those moments stay with you, just like a shepherd always stays a shepherd.

Even now, in a world of drones and GPS collars, the dog trial holds its place. Because while farming may change, the bond between a shepherd and a good dog—built on whistle, instinct, and trust—is timeless.

The Booth, the Banter, and the Baa.

Store lambs for sale at the Temuka Saleyards.

On Tuesday, I’ll head to the Temuka sale yards for the weekly sheep sale. I’ve no urgent business there, but that’s hardly the point. You go for the same reason you go to a cousin’s wedding or an old mate’s funeral. You might not have a direct role to play, but something in you says: show up. The yards still hum with that same mix of business and theatre, lanolin and bullshit, that hooked me as a kid.

I grew up beside the Geraldine Sale Yards. Every February, the Ewe Fairs would roll into town like clockwork. After school, we’d hover around the pens hoping to cadge a ride in a stock truck. For us kids, the sheep were secondary to the machinery and mystery of it all: the auctioneers with their fast mouths and faster pencils, the shepherds with their felt hats pulled low and hands tucked into weathered pockets, the booth with its spilt beer and louder lies. We weren’t allowed near the beer tent, which of course made it even more intriguing. You could hear the laughter from the other side of the pens: laughter with teeth in it.

Stock agents were gods in that world. Flashy ties, Aertex shirts, fast talkers, boots that never got dirty, no matter how wet the yards were. They’d stride from pen to pen, clutching sheaves of paper with rows of tallies and names, closing deals with a wink, a nod, and a slap on a leather-bound stock book, then vanishing into the booth like stage magicians.

Later, when I became a shepherd myself, stock sales became more than just a spectacle; they became part of the social calendar. My shepherd mates and I would swing into the Tekapo Sale with utes full of dogs, with sheep from Grampians, Dry Creek or Blue Mountain on offer. We would follow the auctioneers, record the prices in our PGG notebooks, and discuss sagely with the old hands. And there was always plenty of time for a beer and a yarn.

I was there in the years when record yardings were on sale and the after-sale piss-ups were on a monumental scale. I’ve been to sheep sales in Wales, China, Australia and England, and the funny thing is, it’s almost always the same. The same hats. The same haggling. The same gruff banter under breath that says more than any formal contract ever could.

While researching this story, I came across the following passage in a book called Shepherd Lore, about the Tan Hill Fair in Wiltshire in the 1930s. It reads like a distant cousin of our own ewe fairs:

“There were ‘roughish crowds’ even at Tan Hill… ‘Diddikais,’ as Wiltshiremen call gypsies, by the score, shouting and quarrelling… shady dealers, garrulous quacks, pickpockets and light-fingered gentry…”

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it? Swap the quacks for stock agents, and you’d be hard-pressed to tell Tan Hill from Temuka.

The best bit? The story of the beer tent. Everyone who attended Tan Hill seemed to remember one thing: the time the tent blew down in a gale. “Yes, I were there when the tent blowed down!” they all say in the story. The tent in question, lovingly referred to as “the boozer,” had collapsed mid-session, scattering farmers, bottles, barrels and beer like bowling pins. No one was hurt, but by all accounts, the bedlam beneath the canvas was biblical.

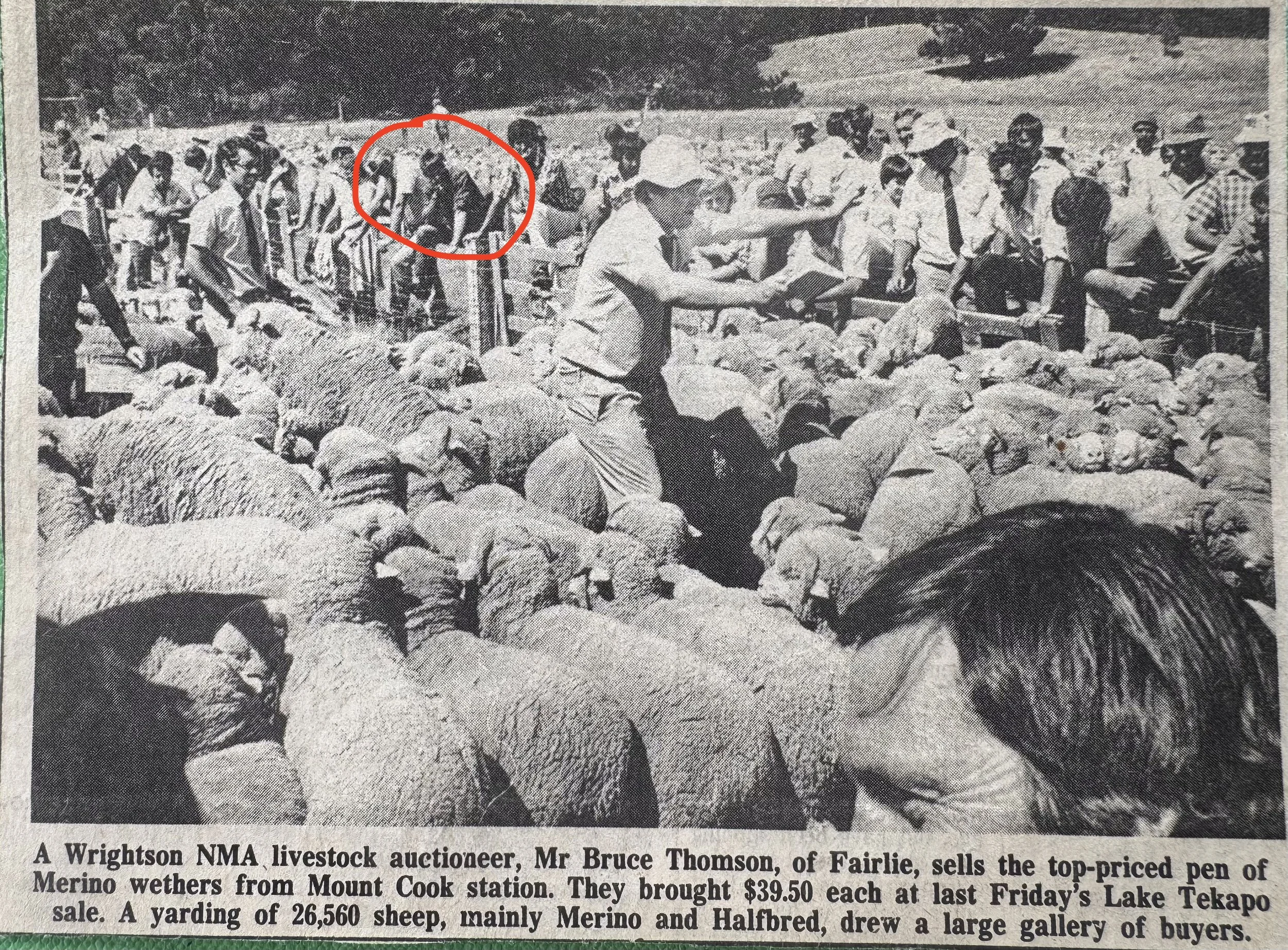

The Tekapo Sale, 1984. This clipping is from the Timaru Herald. The young fellow (circled), looking sagely at the yarding, is me.

We had our own versions of that at Tekapo, Geraldine, and Albury. Some were accidental: wind, rain, a Toyota 4WD full of stud rams tipped over on a back street, an argument with a pompous stock firm manager, bitches lined with dogs behind the shed, the occasional fist fight, drunken shags on the seats of parked utes, broken glass, burnt sausages, and long nights of bullshit and yarns.

Others were planned: the kind of planned chaos that happens when a day’s hard trading meets a night’s easy drinking. I’ve seen shepherds leap fences in pursuit of a wagered bottle. I’ve watched grown men auction off a crate of Speights with the solemnity of a ram sale. Once, I saw a stock agent buy his own socks back after losing them in a game of cards in the booth.

The Abergavenny sheep sale, 1990.

In the summer of 1990, I attended the Abergavenny Sheep Sale. Back then, the market was still held in its original location: an indoor warren of concrete pens and laneways echoing with the cries of auctioneers, the clatter of hooves, and the sharp tang of sheep shit in the air. It was a crowded, frenetic affair: local farmers jostled shoulders with livestock dealers, all of them clutching catalogues and bacon rolls, dogs barking from the backs of battered Land Rovers outside. I remember the chaos and familiarity of it, the shared language of nods, bids, and terse remarks about the condition of the stock. It was, in its way, a ritual: part business, part theatre, entirely embedded in the fabric of rural life.

In 2025, I returned to that same location out of curiosity, only to find the old sheep market transformed. The pens and auctioneers’ rostrum were long gone, replaced by artisan stalls, espresso machines, and displays of handmade soaps and sourdough. The building now housed a bustling craft market, filled with bric-a-brac, vintage clothing, and lively chatter. It was charming, even lovely, but the smell of sheep was gone. The livestock market itself had moved to a purpose-built facility at Bryngwyn near Raglan, the result of years of transition following the Foot & Mouth crisis and the eventual closure of Newport and Monmouth markets. As I sipped my flat white in what had once been the main sale ring, I felt the strange passage of time: the world changes its clothes, but you never forget what it used to wear.

The Abergavenny Market Building, June 2025.

Sheep sales, for all their commercial intent, have always been more than just a place to move stock. They’re waypoints. Social summits. Places where news is passed along faster than through any official channel. Where the price of wool, the rumour of a dry summer, or a neighbour’s death are all spoken of with the same tone: quiet, informed, matter-of-fact.

They’re changing, of course. Everything is. Sales are slicker now. More screens, less smoke. Dogs are left in the ute. The old booths are either banned or gentrified into tidy cafés selling flat whites and gluten-free muffins. But still, the core remains: sheep, mud, handshakes, and that unspoken code between people who know what it means to raise something, and let it go.

So I’ll be at Temuka on Tuesday. Not to buy or sell, but to bear witness. To see who’s there. To count the dogs in the back of the utes. To listen to the echo of the past in the auctioneer’s voice and the crackle of the loudspeaker. And maybe, if I’m lucky, to overhear someone say: “I were there when the booth blew down.”

Because some stories are too good not to repeat.

Loading sheep at the Tekapo Saleyards in the 1960s.

Meat

The killing shed at Grampians smelled of iron and shit and steam. It was a place of hard floors and harder men, of old blood gone black in the corners and fresh blood running in ribbons toward the drain. You didn’t flinch here. You worked. You learned. You kept your knife sharp and your mouth shut.

Peter Kerr and I once had a race to see who could skin a mutton fastest. Unofficial, like most things in the yard, but the stakes were real. Pride. Skill. The silent hierarchy of the shed. Kerr was a surgeon with a knife. He’d learned from his father, back in the days when freezing works ran on sweat and edge, not conveyors and air guns. But I was young. Fast. Strong. And, unknowingly, his student.

We started side by side. Two sheep, hanging from the hooks, legs twitching with the ghost of muscle memory. No words, just movement. Blades flashing, hide peeling in long, practised pulls. Then I slipped. A deep slice, left forefinger. Blood everywhere. Thick, dark, venous. For a second, I pressed on. But the knife slipped again. I stopped. Kerr didn’t. He won. No gloating. Just that same steady look.

Later, after stitches and a nurse with hands like cold steel, Kerr told me I’d done it on purpose because I knew I was losing. He laughed. So did I. But I didn’t forget. I still have the scar. A thin white line on my left forefinger. I see it every day. It reminds me. Because meat, like wool, is the product of care. But it begins with death.

Lambs are born in spring: soft, bright-eyed, full of bounce. By summer, they’re grazing heavily on pasture and grain. By autumn, decisions are made. Some go to market. Some stay. Some are kept to breed. Others walk into the killing shed.

I learned to kill properly. Quickly. Cleanly. No panic. No cruelty. The throat cut must be sure, the drop immediate. Then comes the work: skinning, gutting, breaking down the carcass. I could do it in under seven minutes. Still can. The cuts: leg, shoulder, loin, rack, shanks. Offal, fat, bones, guts to cook up for the dogs. Nothing wasted. Every part used. That’s how shepherds feed themselves, their families, their dogs, and, sometimes, their communities.

But it’s the cooking where memory lives. In New Zealand, we ate lamb chops grilled over glowing embers in musterers' huts, the fat dripping into the flames. We slow-cooked mutton in camp ovens over fires in snow-fed huts. The taste of it wasn’t just in the meat: it was in the smoke, the cold, the laughter, the dogs curled asleep nearby.

In Mongolia, it is boiled sheep, bone-in, meat and fat pulled apart with fingers, eaten on the floor of a felt-walled ger. No seasoning, just salt and steam. Felt underfoot, the wind outside billowing like the sea. The sheep, like the people, lean and tough from the steppe.

In Jordan, they eat whole lamb, stuffed with rice and nuts and spiced yoghurt, pulled steaming from a sand oven. This is mansaf, eaten communally, from a single platter, with right hands only, bread as a spoon. The heat, the aroma, the quiet reverence of the elders. It is as much a ceremony as a meal.

In Oman, beside the campfires of Bedouin herders, the carcass of a black goat is split open and splayed above a fire. Smoke clings to the robes and hovers in the still air. The meat is soft, deeply spiced, and eaten with torn bread and bitter coffee. No cutlery. No plates. Just hands, sand, and stars.

In the Atlas Mountains of Morocco, shepherds share skewers of liver and fat, grilled over roadside coals. In Georgia, mountain families eat khinkali stuffed with lamb and herbs: meat pockets that burst like memory. In Wales, it is lamb cawl: a humble stew with potatoes and leeks, thick as fog and just as comforting.

Same animal. Different dress. Same story: a life raised with care, ended with skill, shared in fellowship. Meat binds people. It’s divided. Eaten with fingers or forks, in silence or song. It marks celebration. It marks death. It marks survival.

And the shepherd knows this. He or she understands that to raise an animal is to live with its rhythm. That death is not the opposite of care; it’s the companion of it. You don’t flinch. You do the job. Quickly. Quietly. With skill. With respect.

Because the body remembers. Not just the land or the plate, but your own flesh. Calluses. Scars. The smell that never quite washes out. Mine is on my left forefinger. A ghost of a race I almost won. A reminder of the cost of learning.

So when I eat lamb now, I remember. Not just the meat. But the dog beside me. The wind in the gully. The call of a shepherd two ridgelines away. The fire. The cold. The care. The blood. Because meat isn’t just food. It’s memory. And memory, like meat, must be carved with care.

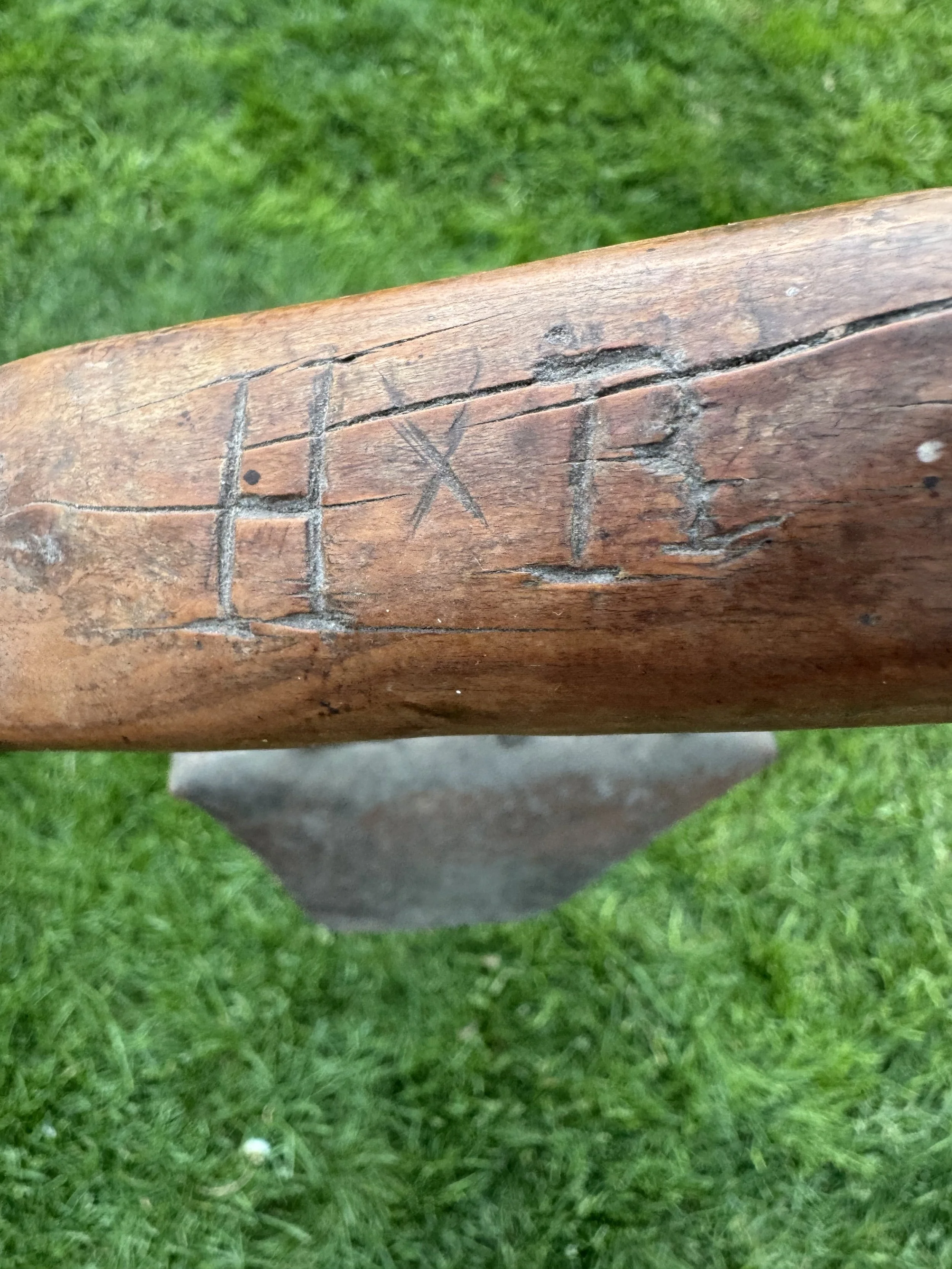

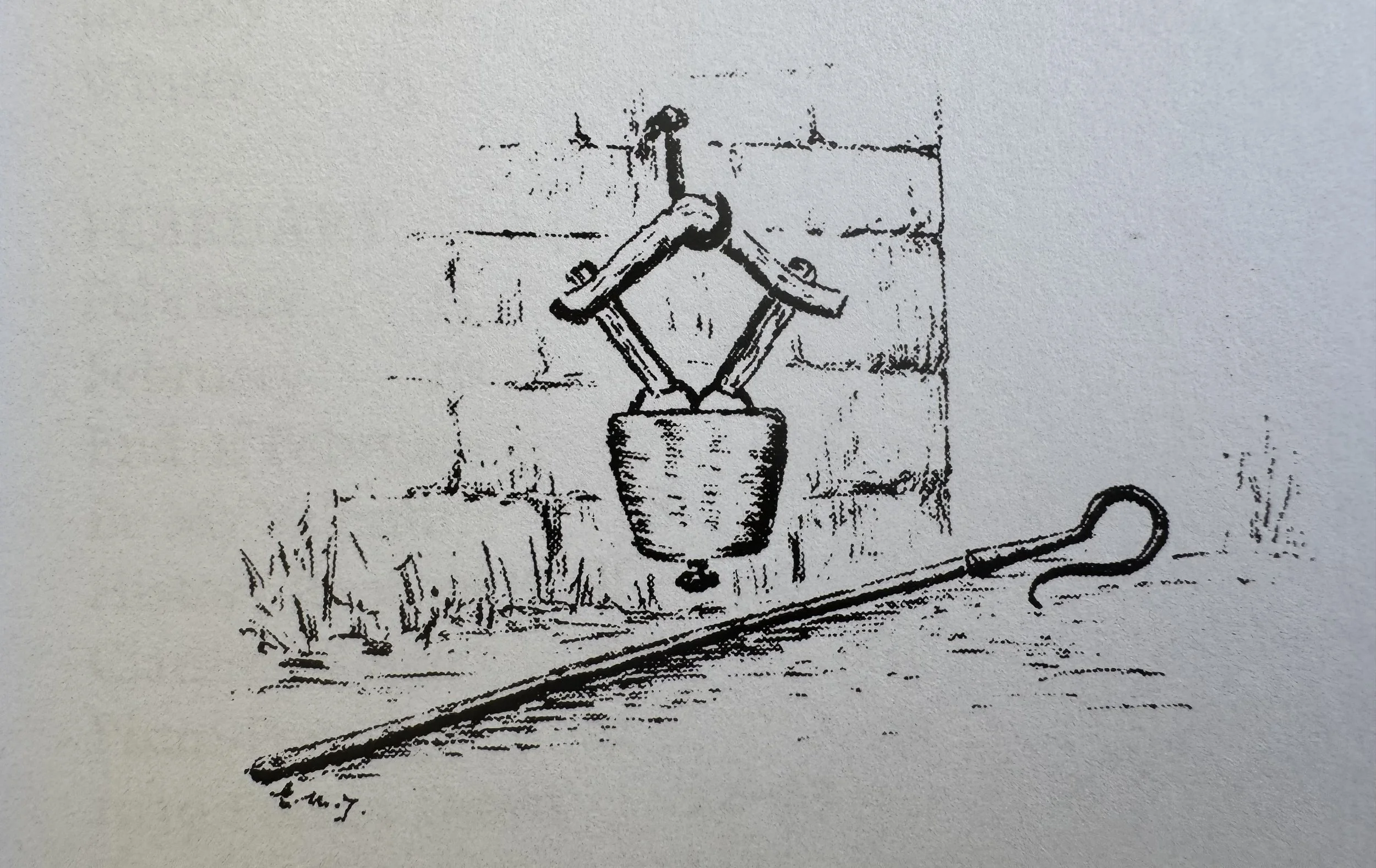

The Cannister Bell

It hangs from a beam on my porch now, weathered and worn: a squat, rusted canister bell with a voice like memory. It came from Wiltshire, a gift from my aunt, Ann, Lady Blakiston, who was once a shepherdess during the war years when all the men were away. She worked the hills of Wiltshire with a crook in one hand and the weight of the land in the other, and brought with her a lifetime of stories: folk tales thick with dew, thick with the kind of truth that only oral history dares tell.

The bell itself is carved with the date 1877 and the initials HR. Whoever that was, I like to imagine he (or she) walked the chalk downs above the Wylye Valley with a few hundred Dorset ewes, and a dog that knew its business. There’s something in the heft of the bell that speaks of labour, of honest days and cold mornings, of lanolin-slick fingers and the wind off Salisbury Plain. The clapper still rings, sharp and metallic, a sound that would carry far over heather and bracken. It’s a sound that sheep come to know: half warning, half lullaby.

In Wiltshire, sheep bells weren’t just tools. They were talismans. Each flock might have just one or two—“leaders’ bells” they were called—hung around the necks of the lead ewes to help the shepherd keep track of his mob in fog, mist, or the failing light of an English dusk. In valleys where the mist pools like water and every hill looks the same, the bell was a lifeline. A way to find your sheep when sight failed and instinct took over.

There’s a Wiltshire tale my aunt used to tell about bells. She claimed that in the days before enclosure, when the land was open and the shepherds knew every blade of grass by name, bells weren’t just for sheep. They were for spirits, too. At lambing time, when the boundary between life and death seemed thinnest, bells were rung not only to locate ewes, but to ward off the “lantern men.” These ghostly figures wandered the downs with lights in their hands, luring lost shepherds to their doom.

“If you heard two bells in the night,” she said, “one was yours, and the other… wasn’t.”

She also believed each bell held a kind of memory. That you didn’t own a bell so much as inherit it. That it rang with all the places it had been and all the sheep it had followed. That’s the sort of thing you smile at when you’re young, and come to believe when you’re older.

Wiltshire itself is sheep country through and through. Before tanks rolled over Salisbury Plain, before Stonehenge was cordoned off behind ropes and placards, it was a place of flocks. Drovers moved their mobs from Devon to London, through the old drove roads of Pewsey Vale and Savernake Forest, resting at chalk-cut watering holes and weather-worn pubs. Bells would clang through village lanes at dusk, and every local could tell by the sound whether the flock was heavy with wool or lean with travel.

The bell that hangs on my porch came through that lineage. A lineage of people who knew how to move quietly, how to listen to the weather, how to count sheep not for sleep but for survival. Aunt Ann was one of those. One of the last, perhaps.

Sometimes, when the wind hits it just right, the bell rings: not loud, just a faint, metallic note in the afternoon breeze. It sounds like a summons. Or a remembering. And each time I hear it, I think of Wiltshire, of Aunt Ann’s stories, of the wartime shepherdess who wore gumboots over stockings and carried her lunch of lardy cake in a nummet bag. I think of the initials HR, carved into the bell with some pocketknife long ago. I think of flocks disappearing into fog. And the soft, certain sound of a bell leading them home.

This pencil sketch of the bell was done in 1986 by E.M. “Betty” Jeans, sister of Ann Blakiston.

The Shepherd’s Dogs

One of the first dogs I ever owned was a scrapper called Mac. It was November 1981. I was a green new-chum shepherd at Grampians, still figuring out what wayleggo meant. Mac fancied himself as a bit of a fighter; he thought he could take on anything on four legs. Unfortunately, his career in the canine fight game was short-lived.

One afternoon, he decided to pick a fight with Storm, Stuart Falconer’s big black-and-tan huntaway. Storm wasn’t just bigger; he was older, meaner, and knew exactly what he was doing. The outcome was about as predictable as a mutton race. Mac went in full of bark and bluster and came out with a nasty hole in his head.

Because he couldn’t reach it to lick, the wound festered and swelled until he looked like he was growing a second skull. The other shepherds, never short of wit or cruelty, christened him “Pussnut.” It stuck. For years, that name followed him across the hills like an echo. But Mac was a tough old boy. He recovered, scar and all, and from then on he picked his battles more carefully: usually with sheep.

Mac…not a fighter.

That was my first real lesson in shepherding: every dog, no matter how brave, learns humility sooner or later. And in a way, that’s what makes them such extraordinary companions.

For as long as shepherds have walked the hills, dogs have walked beside them: partners in patience, courage, and the occasional foolishness. Their history stretches back millennia, to when early herders first noticed that the wolves hanging around the campfires could be persuaded to work for a living. From that uneasy truce came the most significant working partnership in history: man and dog, mind and instinct, whistle and bark.

Every shepherd knows the feeling of watching a good dog at work—the way it moves with quiet intent, crouched low, reading both sheep and master. There’s no need for words. A whistle, a glance, and the job’s done.

Jill, my heading dog, with trophies that she won at the Burke’s Pass Dog Trials, 1987.

I’ve had many dogs since Mac, each with their quirks, tempers, and triumphs. Some barked too much, some thought too much, and a few, like Mac, mistook bravado for brains. But every one of them shared the same heartbeat—the same devotion to the job, the same bond that has tied shepherds and dogs together since before the first fence was built.

The truth is, shepherding without dogs would be like fishing without water. They make the work possible, and more than that, they make it worthwhile. They remind you that intelligence comes in all shapes: sometimes with four legs, a cold nose, and a ridiculous nickname you’ll never live down.

🐑🐑🐑🐑🐑🐑🐑

In every shepherd’s story, there are dogs. Faithful, cunning, and uncomplaining, the sheepdog has been part of the shepherd’s life for thousands of years; long before crooks and quad bikes, before fences, before plastic whistles and GPS.

Archaeologists have found the bones of herding dogs beside their masters in Neolithic graves, their remains suggesting a partnership already ancient by the time the first flocks grazed the highlands of Britain. From the Middle East to Mongolia, from the Pyrenees to New Zealand’s Mackenzie Country, the pattern repeats: shepherds and dogs, side by side, reading each other’s minds in the language of work.

A good dog is more than a helper. They are an extension of the shepherd’s will: seeing what their master cannot, moving with an intelligence that feels half instinct, half intuition. Together they form a single working mind, divided only by distance and whistle.

Border Collies, Wales.

The bond between shepherd and dog is unlike any other. It’s forged in weather and work; long days on the hill or in the desert, wet and wind-blown, hot and thirsty, where a nod or a glance says more than a dozen words. There’s pride in a well-cast dog, in the way it circles the mob with that low, wolfish run, or crouches, eyes locked, until the sheep turn and yield.

Across the centuries, countless breeds have emerged from this shared labour: the wiry little Welsh Collie, the lithe Bearded Collie of the Highlands; the stalwart Huntaway of New Zealand, bred not for silence and stealth but for sound, a booming bark that moves thousands. In Andalusia, the Perro de Agua guards flocks against wolves; in Turkey, Kangals stand guard beneath the stars; in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco, the Aidi keeps the flock safe from jackals; and on the steppes of Mongolia, the great Bankhar dog sleeps beside the herder’s yurt, ever watchful.

Kangal sheepdogs, Turkey.

Yet no matter their shape or voice, they carry the same inheritance: loyalty, endurance, and the quiet joy of purpose. Every shepherd has a dog story. Dogs who saved a drifting mob in the fog, or brought a runaway ewe down from the cliffs of Snowdonia. Dogs who outsmarted belligerent rams on the Canterbury Plains, dodged hooves on the red soils of Andalusia, and worked until they could barely stand on the peaks overlooking the Black Sea. Dogs who refused to be left behind in the dust of the Outback, or in the snowfields of the Caucasus.

These stories are the truest measure of a shepherd’s life. Because behind every tally, every muster, every long droving route, every hot day in the yards, every desert morning, every campfire on the Mongolian steppe, every snowbound night in the Caucasus, every wind-swept hill in Wales, every dawn call to prayer echoing across the deserts of Jordan, and every thunderstorm rolling over the plains of Central Queensland, a dog is watching, waiting, ready to work again.

Bounce, Four Peaks Station, 1994.

Introduction to The Shepherds

It all begins with an idea.

I am a shepherd.

There. I’ve said it.

I am a shepherd.

Being a shepherd is a bit like being a surfer. Or being in the Mafia. Or a being ordained as a monk. Once you're in, you're never really out. The life stays with you. It shapes how you move through the world. And although more than a quarter of a century has passed since I last walked the muscular hills and ridges of the High Country on New Zealand’s South Island, with dogs at my heels and a manuka stick in my hand, the imprint of those years remains as clear to me as the tracks on a snow slope.

It’s a young man’s calling, shepherding. I began at eighteen. As I grew older, I moved on—seeking new places, new pursuits—but the qualities I gained from that life have never left me. Resourcefulness, independence, and self-reliance. To be observant. To have an eye for weather, and a respect for solitude. These are not just skills; they are ways of being. And now, as my TikTok feed fills with the sights and sounds of shepherds from Turkey, Kazakhstan, Arabia, Wales, China, Morocco, Scotland, Georgia, Spain and New Zealand—ShepherdTok, I call it—I find myself once again drawn into that world I once inhabited. A world I never really left.

Merino wethers crossing the Hakataramea Pass, Grampians Station, 1986.

So I’ve come back: not as a shepherd this time, but as a witness. A chronicler. A traveller with a dog whistle still hanging on a lanyard around my neck, a small token of a life once lived and never truly left behind.

I am not returning to muster sheep this time. I am coming back to gather up stories. I want to walk along the ridgelines of my memory, and the mountain paths and desert trails walked by other shepherds. I want to revisit my former life as a shepherd with the clarity that only age and distance can bring. I want to examine what I did in those far off days, who I was, and how being a shepherd shaped who I became.

But this journey is not mine alone. I want to explore the ancient world of shepherds; men and women who walked before me, crook in hand, through the pages of history and scripture. From the hills of Judea to the fells of Cumbria, from the Mesta trails of Spain to the steppes of Central Asia, shepherds have long stood as figures of resilience, watchfulness, and quiet authority.

And more than anything, I want to connect with shepherds across the world today. To hear their voices, learn their rhythms, and understand the land through their eyes. Whether herding flocks in the Atlas Mountains, minding ewes in the Pamirs, or watching over mobs in the Welsh hills, these men and women speak a language I still recognise: a language of wind, of silence, of movement, and care.

This is my return. Not to the fold, but to the field. To walk beside shepherds once more. Across cultures, across time, and across the great, weathered face of the Earth.

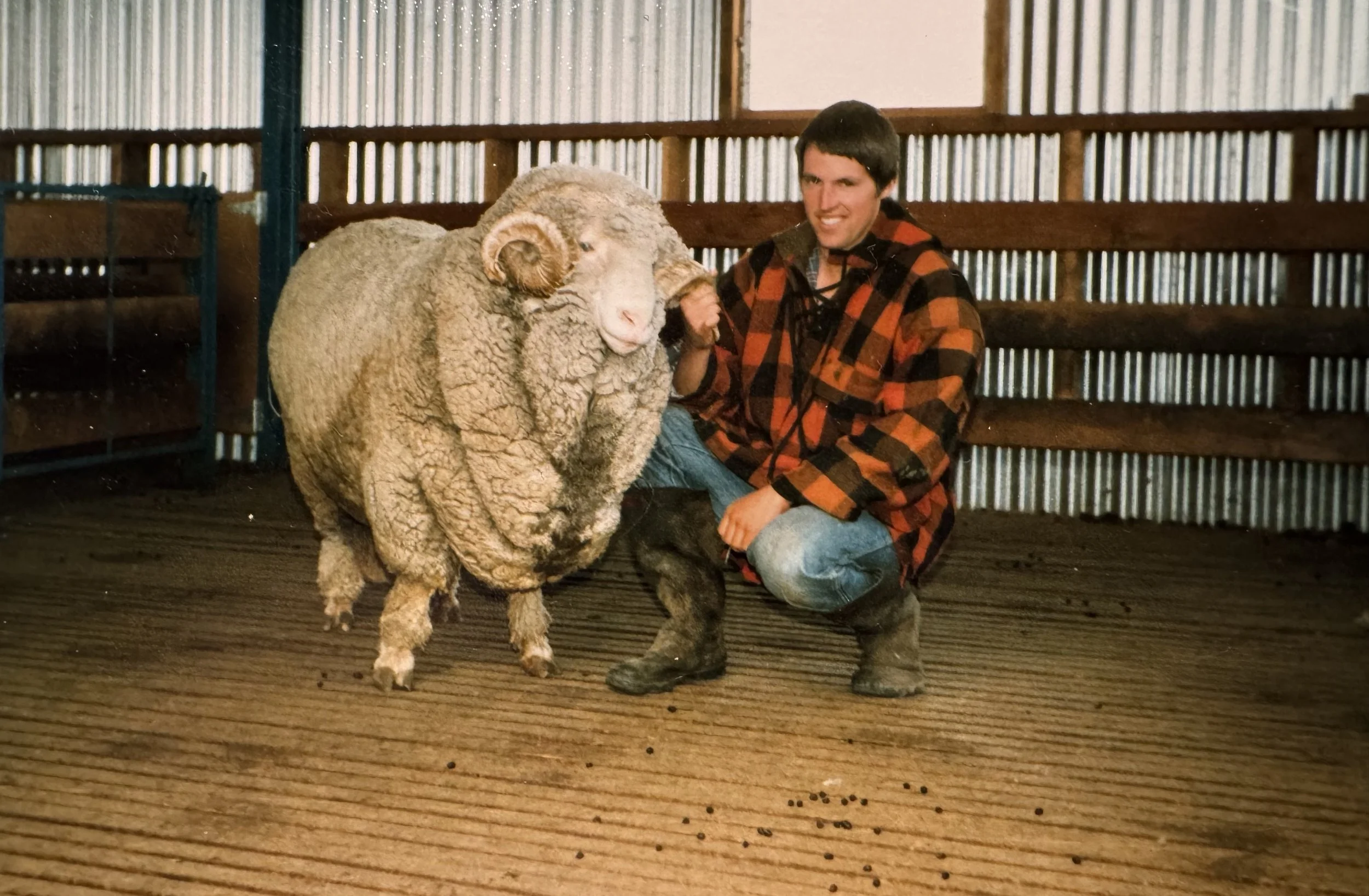

The author with a prize-winning merino ram, Grampians Station, 1985.