The Booth, the Banter, and the Baa.

Store lambs for sale at the Temuka Saleyards.

On Tuesday, I’ll head to the Temuka sale yards for the weekly sheep sale. I’ve no urgent business there, but that’s hardly the point. You go for the same reason you go to a cousin’s wedding or an old mate’s funeral. You might not have a direct role to play, but something in you says: show up. The yards still hum with that same mix of business and theatre, lanolin and bullshit, that hooked me as a kid.

I grew up beside the Geraldine Sale Yards. Every February, the Ewe Fairs would roll into town like clockwork. After school, we’d hover around the pens hoping to cadge a ride in a stock truck. For us kids, the sheep were secondary to the machinery and mystery of it all: the auctioneers with their fast mouths and faster pencils, the shepherds with their felt hats pulled low and hands tucked into weathered pockets, the booth with its spilt beer and louder lies. We weren’t allowed near the beer tent, which of course made it even more intriguing. You could hear the laughter from the other side of the pens: laughter with teeth in it.

Stock agents were gods in that world. Flashy ties, Aertex shirts, fast talkers, boots that never got dirty, no matter how wet the yards were. They’d stride from pen to pen, clutching sheaves of paper with rows of tallies and names, closing deals with a wink, a nod, and a slap on a leather-bound stock book, then vanishing into the booth like stage magicians.

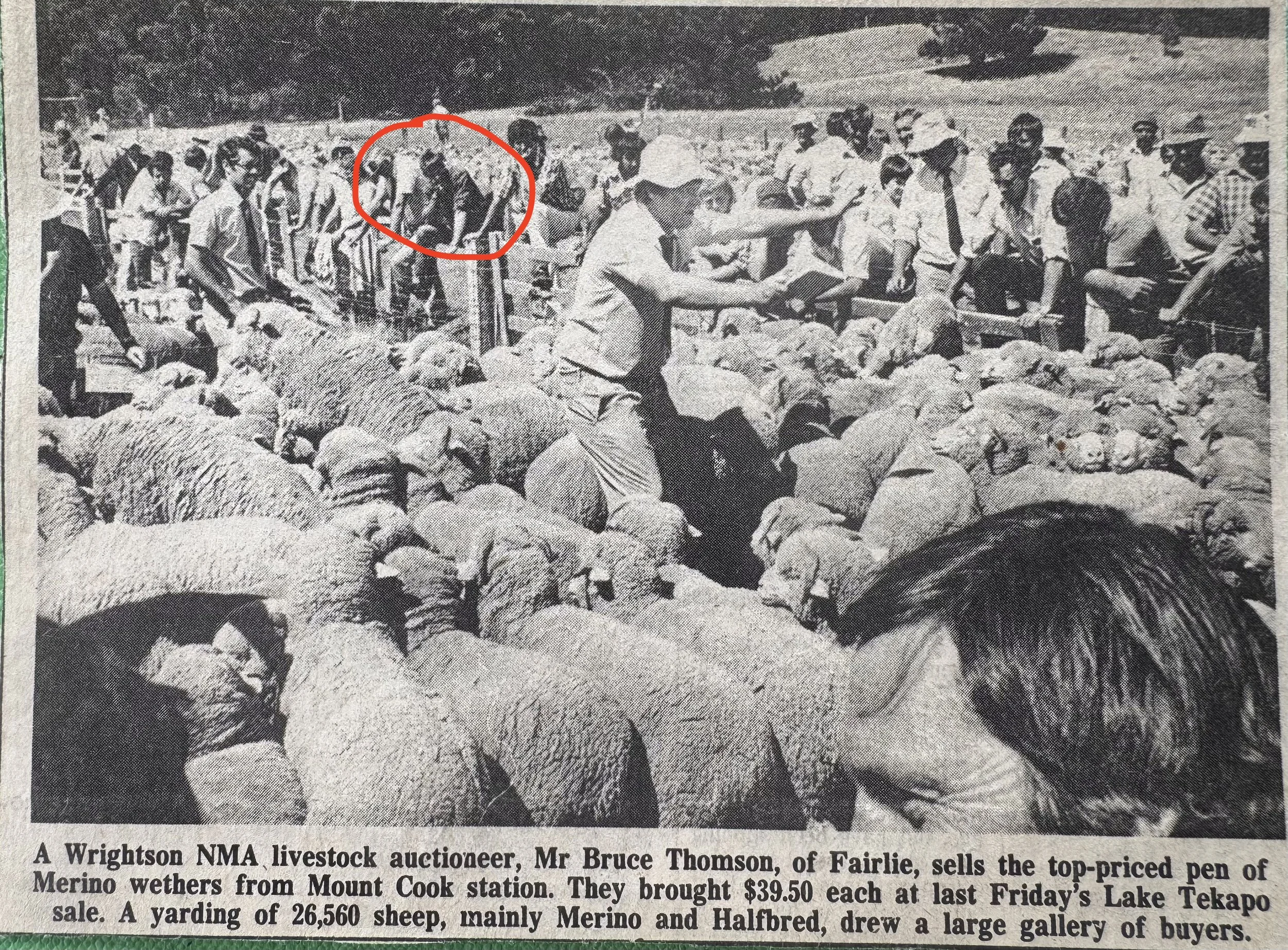

Later, when I became a shepherd myself, stock sales became more than just a spectacle; they became part of the social calendar. My shepherd mates and I would swing into the Tekapo Sale with utes full of dogs, with sheep from Grampians, Dry Creek or Blue Mountain on offer. We would follow the auctioneers, record the prices in our PGG notebooks, and discuss sagely with the old hands. And there was always plenty of time for a beer and a yarn.

I was there in the years when record yardings were on sale and the after-sale piss-ups were on a monumental scale. I’ve been to sheep sales in Wales, China, Australia and England, and the funny thing is, it’s almost always the same. The same hats. The same haggling. The same gruff banter under breath that says more than any formal contract ever could.

While researching this story, I came across the following passage in a book called Shepherd Lore, about the Tan Hill Fair in Wiltshire in the 1930s. It reads like a distant cousin of our own ewe fairs:

“There were ‘roughish crowds’ even at Tan Hill… ‘Diddikais,’ as Wiltshiremen call gypsies, by the score, shouting and quarrelling… shady dealers, garrulous quacks, pickpockets and light-fingered gentry…”

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it? Swap the quacks for stock agents, and you’d be hard-pressed to tell Tan Hill from Temuka.

The best bit? The story of the beer tent. Everyone who attended Tan Hill seemed to remember one thing: the time the tent blew down in a gale. “Yes, I were there when the tent blowed down!” they all say in the story. The tent in question, lovingly referred to as “the boozer,” had collapsed mid-session, scattering farmers, bottles, barrels and beer like bowling pins. No one was hurt, but by all accounts, the bedlam beneath the canvas was biblical.

The Tekapo Sale, 1984. This clipping is from the Timaru Herald. The young fellow (circled), looking sagely at the yarding, is me.

We had our own versions of that at Tekapo, Geraldine, and Albury. Some were accidental: wind, rain, a Toyota 4WD full of stud rams tipped over on a back street, an argument with a pompous stock firm manager, bitches lined with dogs behind the shed, the occasional fist fight, drunken shags on the seats of parked utes, broken glass, burnt sausages, and long nights of bullshit and yarns.

Others were planned: the kind of planned chaos that happens when a day’s hard trading meets a night’s easy drinking. I’ve seen shepherds leap fences in pursuit of a wagered bottle. I’ve watched grown men auction off a crate of Speights with the solemnity of a ram sale. Once, I saw a stock agent buy his own socks back after losing them in a game of cards in the booth.

The Abergavenny sheep sale, 1990.

In the summer of 1990, I attended the Abergavenny Sheep Sale. Back then, the market was still held in its original location: an indoor warren of concrete pens and laneways echoing with the cries of auctioneers, the clatter of hooves, and the sharp tang of sheep shit in the air. It was a crowded, frenetic affair: local farmers jostled shoulders with livestock dealers, all of them clutching catalogues and bacon rolls, dogs barking from the backs of battered Land Rovers outside. I remember the chaos and familiarity of it, the shared language of nods, bids, and terse remarks about the condition of the stock. It was, in its way, a ritual: part business, part theatre, entirely embedded in the fabric of rural life.

In 2025, I returned to that same location out of curiosity, only to find the old sheep market transformed. The pens and auctioneers’ rostrum were long gone, replaced by artisan stalls, espresso machines, and displays of handmade soaps and sourdough. The building now housed a bustling craft market, filled with bric-a-brac, vintage clothing, and lively chatter. It was charming, even lovely, but the smell of sheep was gone. The livestock market itself had moved to a purpose-built facility at Bryngwyn near Raglan, the result of years of transition following the Foot & Mouth crisis and the eventual closure of Newport and Monmouth markets. As I sipped my flat white in what had once been the main sale ring, I felt the strange passage of time: the world changes its clothes, but you never forget what it used to wear.

The Abergavenny Market Building, June 2025.

Sheep sales, for all their commercial intent, have always been more than just a place to move stock. They’re waypoints. Social summits. Places where news is passed along faster than through any official channel. Where the price of wool, the rumour of a dry summer, or a neighbour’s death are all spoken of with the same tone: quiet, informed, matter-of-fact.

They’re changing, of course. Everything is. Sales are slicker now. More screens, less smoke. Dogs are left in the ute. The old booths are either banned or gentrified into tidy cafés selling flat whites and gluten-free muffins. But still, the core remains: sheep, mud, handshakes, and that unspoken code between people who know what it means to raise something, and let it go.

So I’ll be at Temuka on Tuesday. Not to buy or sell, but to bear witness. To see who’s there. To count the dogs in the back of the utes. To listen to the echo of the past in the auctioneer’s voice and the crackle of the loudspeaker. And maybe, if I’m lucky, to overhear someone say: “I were there when the booth blew down.”

Because some stories are too good not to repeat.

Loading sheep at the Tekapo Saleyards in the 1960s.