Copper Memories and Silver Plates

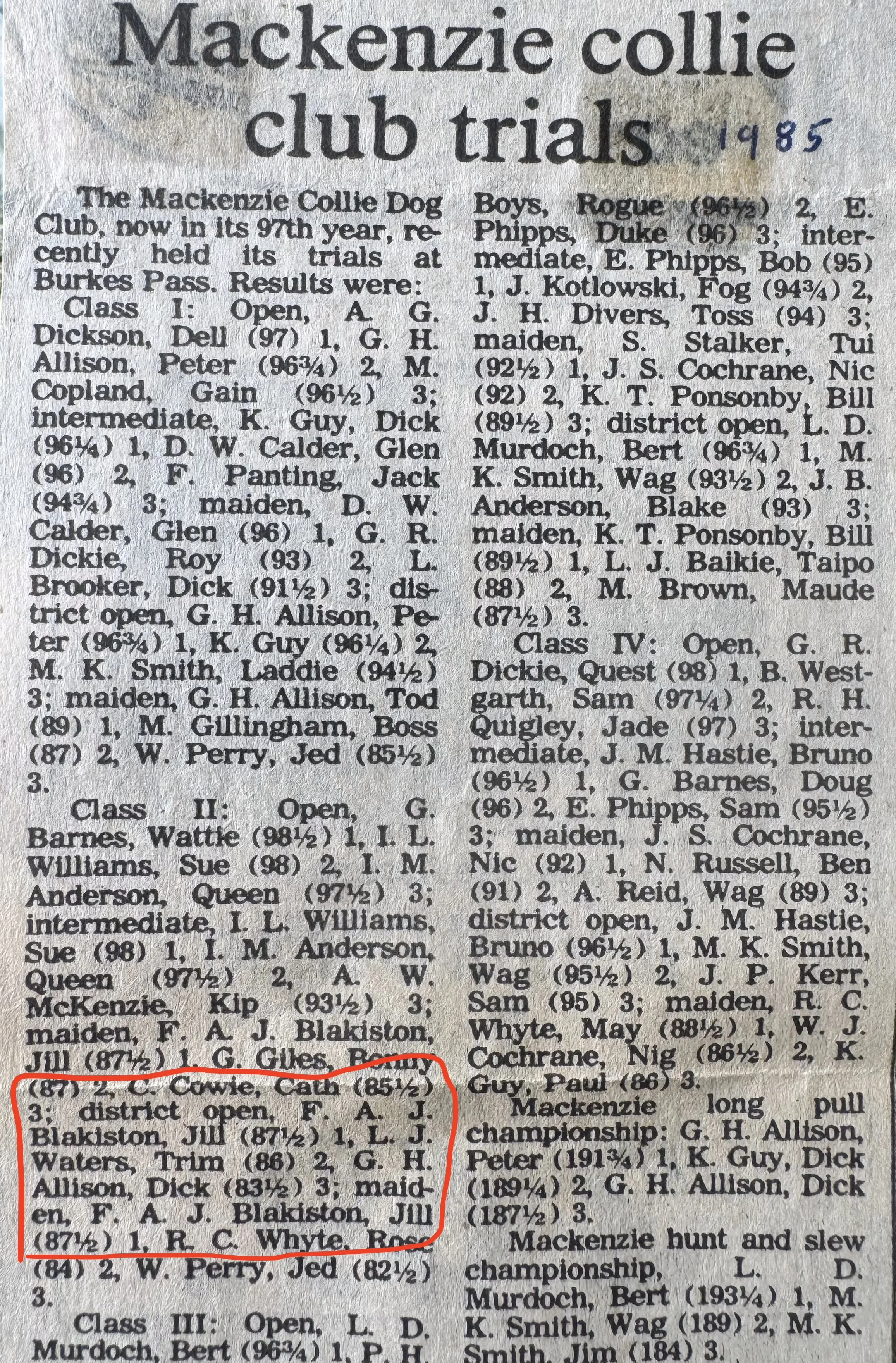

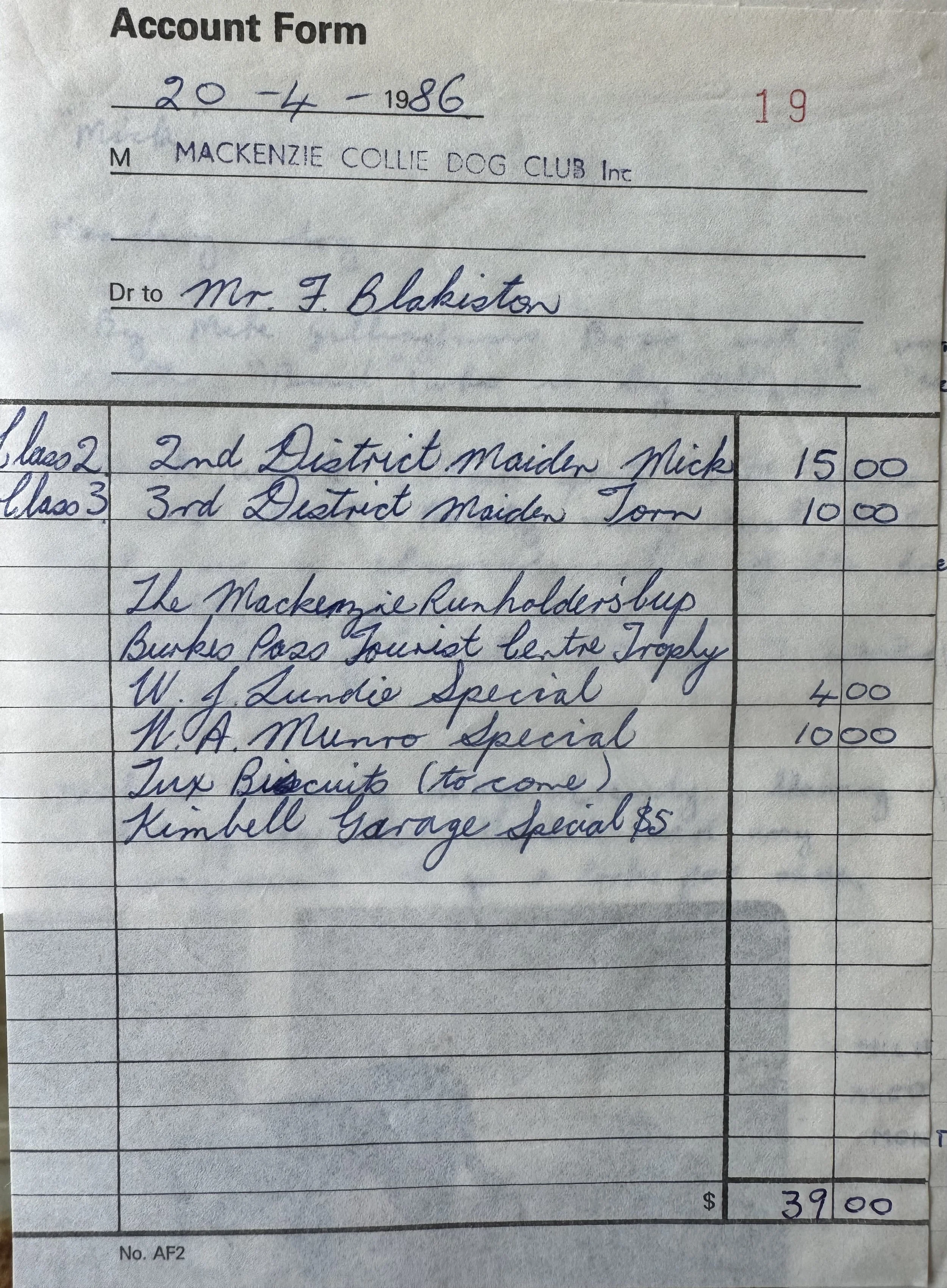

Jill and the trophies she won at the Mackenzie Collie Club Trials in 1985.

In the Kimbell Pub, on the wall beside the pool table, hang two copper plaques. Their surfaces are dark with age, polished only where fingers have traced the names. They once hung on the wall beside the bar in the Burke’s Pass Pub: before the fire, before the roof collapsed, before the only thing to make it out unscathed was the dog trial memorabilia. The exact cause of this is still a mystery. Maybe the old gods of the hill country have a soft spot for collies and triallists.

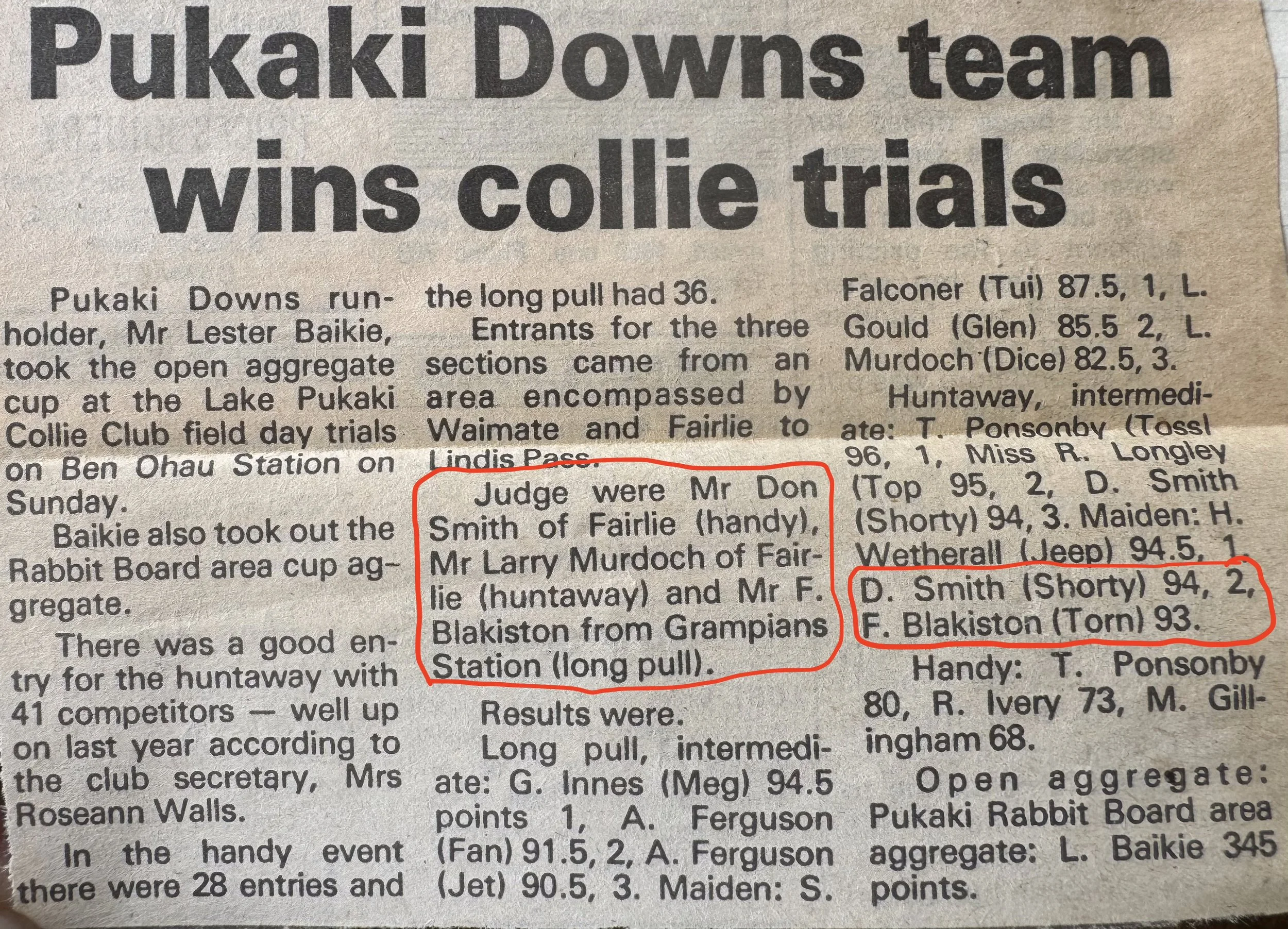

Those plaques carry history in every engraved line. They bear the names of all the shepherds who have won open titles at the Mackenzie Collie Club Trials. Names I remember: Geoff Allison, Tony Wall, Stuart Falconer, Ian Anderson, J.P. Kerr, Bruce Westgarth, Larry Murdoch. Men I worked with at Grampians, Black Forest, Dry Creek, and Blue Mountain. Men whose dogs could slide a mob through a tight gate without breaking stride. Men who drank their tea black and counted sheep in twos without blinking.

Dogs that I remember, too. Peter Kerr’s Blue was a nasty little tri-coloured brute, but he would whisk three sheep down the course in an eye-blink. Bruce Westgarth’s Stuart was a big, grinning beardie, named after another fellow whose moniker appears on the plaque. And Geoff Allison’s Ken, a world champion eye dog who could stare down the stroppiest ewe and force sheep into the pen by sheer hypnotic willpower.

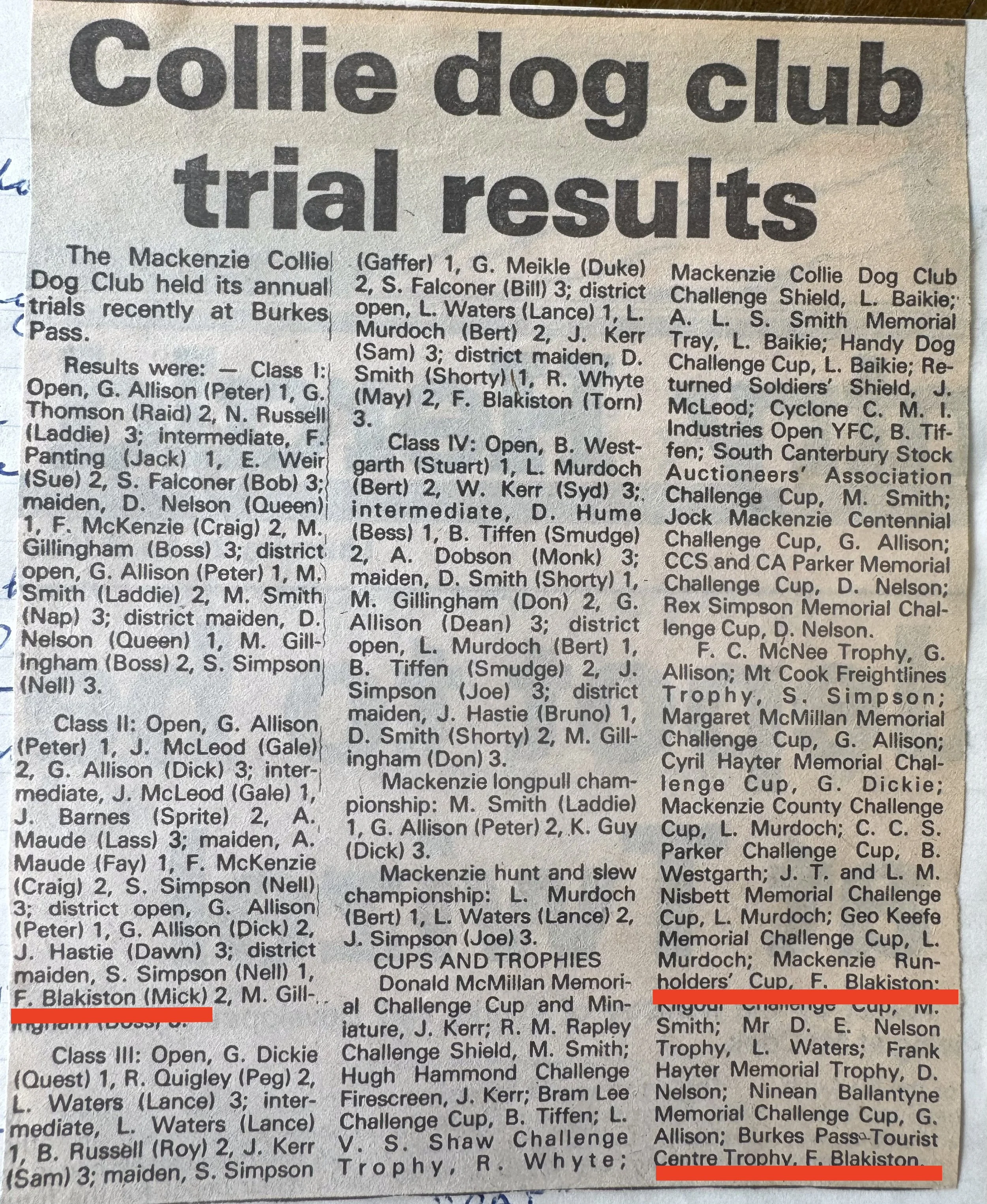

Dog trials weren’t just a sport. They were a measure of a shepherd’s skill, a place where quiet men became local legends for a perfect cast, a clean lift, or a tricky pen done smooth as silk. I earned my own modest place in that lineage with Jill, my quiet-eyed heading dog. We won the plate and cup at the 1985 Burke’s Pass trials. I still have the clippings somewhere—Jill, Tornado, Mick, Bess—all mentioned in print, my name beneath theirs like a footnote.

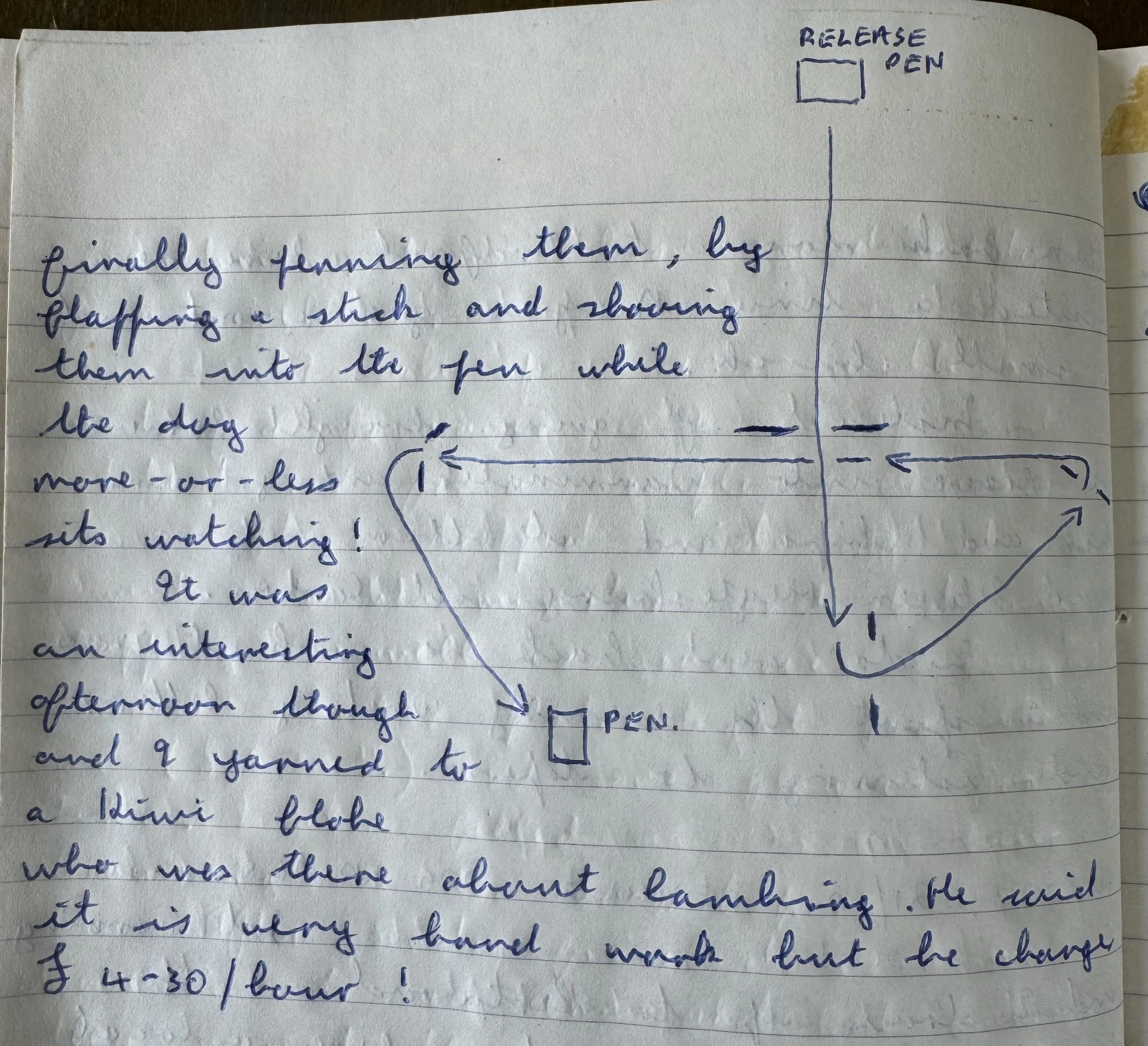

My diary entry for October 10th, 1990.

And there was the Pertwood Dog Trial in Wiltshire, 1990. It was a grey, stormy day, the kind that makes the wind howl through your bones. I drove up to the downs near Warminster, where the trial was being held in a small, wind-snatched valley. The format was simple: pull six sheep down off the hill, drive them through hurdles, then pen them with a stick-flap and a prayer while the dog sits watching.

It was different to the trials at home, but the rhythm and connection were the same. A whistle on the wind and a dog that knows what to do before the sheep do. It’s about the way a good run makes the hair stand up on your arms, and how long after you’ve left the hill, you still hear the bark, the whistle, the slow, steady heartbeat of sheep hooves on damp earth.

Dog trialling began, as most good things do, out of necessity. Long before prizes, plaques, or folding chairs in a paddock, there were just men, dogs, and sheep that needed shifting. The earliest trials didn’t have judges or scorecards—just neighbours gathered to see whose dog could work a mob cleaner, quicker, with fewer shouts and more style.

The first recorded sheepdog trial took place in Bala, North Wales, in 1873. A few Welsh farmers put up prize money and gathered on a hillside to watch dogs do what they’d been doing for centuries. Word spread. The idea caught on, and by the end of the 19th century, trials were being held across the British Isles and, soon after, in the colonies: Australia, New Zealand, and even Canada.

In New Zealand, dog trials arrived with the Scottish shepherds who brought not just their collies but a certain quiet pride in their craft. Out here, the land was wilder, the distances longer, and the weather always a character in the story. Trials became a way to hone skills, share knowledge, and—occasionally—resolve disputes without resorting to violence. They were part competition, part celebration, part confirmation that what we did on the hill mattered.

Clubs were formed. Rules refined. A points system emerged to judge not just success, but style. Trials were divided into events. Class One: the Long Pull; Class Two: the Drive and Yard; Class Three: the Straight Hunt; Class Four: the Zig-zag Hunt. The dogs had to read the sheep, the handler had to read the dogs, and the crowd sat silent, like prayers, watching it all unfold like a chess game played at speed.

By the mid-20th century, dog trials were a fixture in rural calendars. In the Mackenzie Country, they were often the only reason to shave, clean your boots, and put on a decent shirt. Crowds would gather at stations and showgrounds, camp chairs and thermoses in tow, to watch the quiet magic of a good dog at work. The real competitors weren’t just after ribbons. They were after respect; the nod from a fellow shepherd that said, “Hell of a run, mate.”

I still remember the day I won the Class Two Maiden in the 1985 Mackenzie Collie Club trials at Burke’s Pass. It was pouring with rain, and I was the last competitor of the day. Jill ran out in a perfect question mark, lifted the sheep from the hook without a halt, and brought them down the hill at a blistering pace, splashing through puddles and crashing through the matagouri.

We drove the sheep through the hurdles at full speed (I remembered to walk between them myself or else I’d be disqualified) and reached the pen with five minutes to spare. The three sheep circled the pen half a dozen times, but Jill never lost contact with them. And then, out of sheer desperation to escape Jill, the sheep dove into the pen. I closed the gate and bowed to the crowd, or what remained of it: most of the spectators had adjourned to the Burke’s Pass pub by then. But that run won me the plate that year.

And that’s the heart of it all. Those copper plaques on the pub wall, the history of the dog trials, and these small victories that live on in memory. It’s about the rhythm of a dog and a shepherd moving as one, and the stories we tell when we’re back inside, drying off by the fire, with a quart bottle of DB in your hand. In the end, once you’ve run a good dog trial, those moments stay with you, just like a shepherd always stays a shepherd.

Even now, in a world of drones and GPS collars, the dog trial holds its place. Because while farming may change, the bond between a shepherd and a good dog—built on whistle, instinct, and trust—is timeless.