Footrot Flashbacks: The Shepherd’s Long Battle with Lame Sheep.

Foot rot. Even now, the words make my shoulders tense. If you've ever worked with sheep, you know the war. For me, during my years at Grampians Station, foot rot was the perennial enemy: silent, smelly, and soul-sapping. It arrived after Christmas like clockwork, and it never left quietly.

Foot rot is an infectious, highly contagious bacterial disease that affects the hooves of sheep. It thrives in damp, muddy conditions where soft hooves and bacteria make easy companions. It usually starts with Fusobacterium necrophorum, which breaks down the skin and tissue, and is followed by the more damaging Dichelobacter nodosus, which burrows deep into the hoof, causing rot between the toes, lameness, and that unmistakable stink.

Once it takes hold, it can spread through a mob like wildfire. Sheep go lame, graze less, and lose condition. And if you don’t get on top of it fast, you’ll spend the rest of the season chasing limping stragglers through the wet.

Foot trimming in the old Grampians woolshed, January 1983. L-R: N. Harraway, I. Anderson, T. Wall, V “Skippy” Gepp.

At Grampians, the annual battle against foot rot began just after New Year's and often dragged on for months. We’d set up a wooden cradle in the back of the woolshed and spend day after day tipping over ewes and wethers, trimming their hooves back to clean, even edges. Each sheep, each foot, every day.

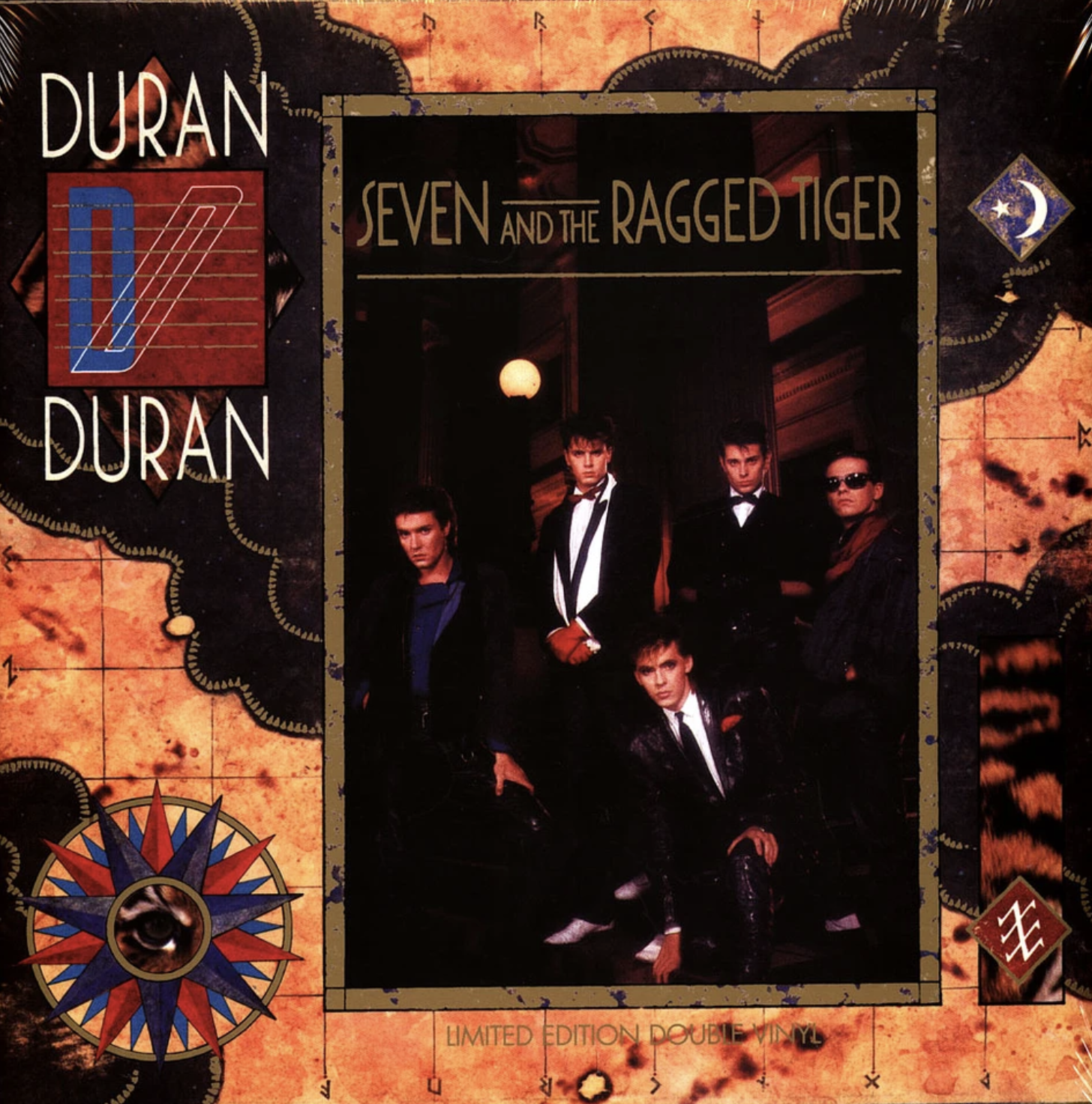

It was mind-bendingly boring, hard, hard work: the kind that leaves a permanent ache in your back and a light dusting of PTSD in your brain. To stay sane, we played cassette tapes nonstop. For me, nothing brings it all back faster than Seven and the Ragged Tiger by Duran Duran. The opening chords of “The Reflex” and I’m there again: elbow-deep hoof trimmings, my paring shears in hand, with the sharp sting of formalin curling through the air like a chemical ghost. Even now, one whiff of it and I half expect someone to hand me a pair of shears and a list of mobs.

And yet… I reckon I could still trim a merino ewe’s hoof back to exactly the right shape, even now, more than forty years since the last time I did it at Grampians. It’s a muscle memory etched into the hands.

After the trimming came the troughing. We’d drag portable footrot baths from paddock to paddock, fill them with a cocktail of water and formalin or zinc sulphate, and run mobs through in a desperate attempt to kill the bacteria and harden their hooves. It worked. Sometimes. But foot rot is nothing if not persistent. One wet week and you were back where you started—like painting the Sydney Harbour Bridge—with paring shears, a sharp pocket knife, and swear words.

Years later, working at Wylie Valley Meats in Warminster, Wiltshire, I had a tidy little side hustle trimming feet for local farmers. I had my own pair of foot rot shears, the experience to use them properly, and a reputation that spread just enough. Hobby farmers would call me up, and I’d head out to trim a few dozen ewes for pocketfuls of pound coins. A bit of sweat, a bit of banter, and enough cash to buy beer and beans for the week.

The only good footrotting shears: long, thin, narrow blades and easy-close spring.

And it wasn’t just me. Years later, reading Shepherd Lore, I came across stories of the old Wiltshire boys and their own “receipts” for foot rot; family formulas passed down and never questioned. One old shepherd swore by a particular green dressing and a special rubber boot to keep the muck out. He had no idea what it was made of, just that it worked.

Another Wiltshire shepherd was quoted as saying: “’T’yent my religion to have lame yeows 'bout. I c’n cure 'em, but t’yent no good messin’ 'bout wi’ the yeows when the be heavy in lamb like theasums.” That makes perfect sense to me. Treat what you can, when you can, but don’t stress a ewe close to lambing just for the sake of tidy feet. Know the rhythm of the job. Timing is everything.

These days, things have improved. Better breeding, better pasture management, and better treatments. But foot rot is still out there, lurking like a bad smell in the wet corner of your memory. Despite all the science and chemicals, foot rot still recurs. The battle goes on.

The shepherd’s life is full of glory in small, quiet moments: on a ridgeline with your dogs, under the stars, during a lambing beat at sunrise. But it’s also about the drudgery, the hard yards in the yards, the weeks bent over hooves, humming Duran Duran and wondering if this will be the year it finally goes away for good. It won’t. But we’ll keep trimming. Keep troughing. Keep scanning the mob for that tell-tale hobble. Because that’s what shepherds do.