The Church of the Good Shepherd

The Church of the Good Shepherd sits amid lupins and tussocks, on the southern shore of Lake Tekapo, with its back to the lake and its face to the Southern Alps.

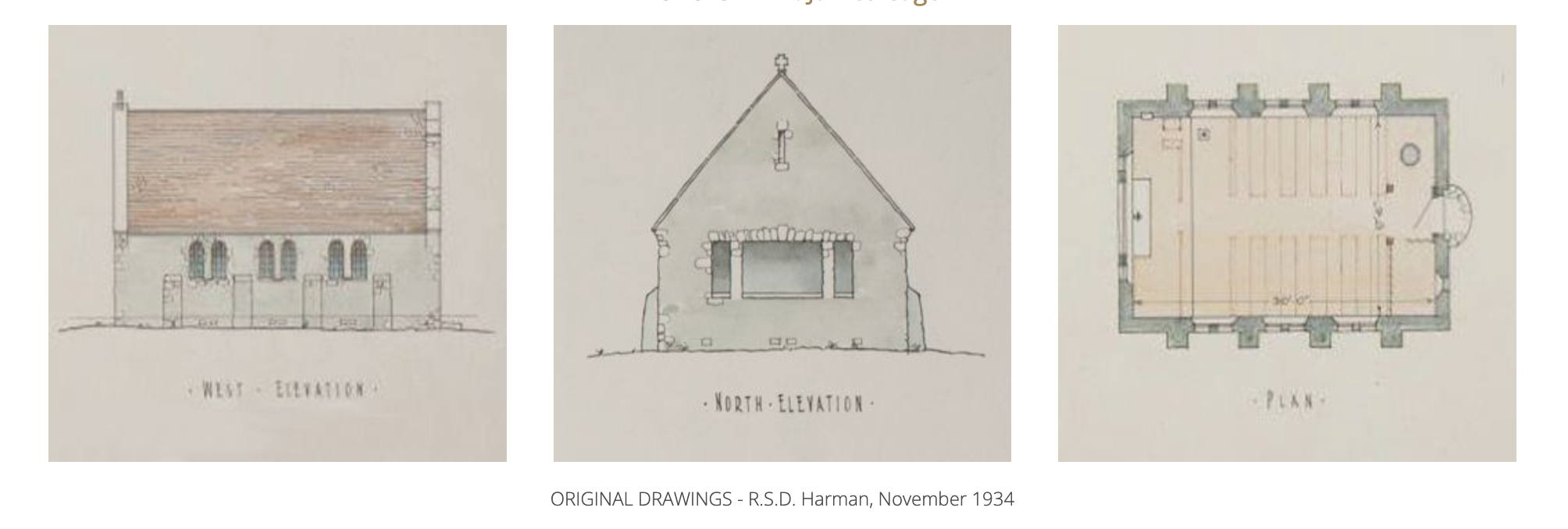

Built in 1935, the church owes its design to drawings by the artist Esther Hope of Grampians Station. These days, the church is a postcard fixture, a must-stop for tourists that has graced social media platforms from Beijing to Walton-on-Thames.

One of the church’s original design remits was that it should not disturb the ground upon which it sits in any way. The brief given to its builders was that no plants or stones were to be moved or removed from the site, and that the stone for its walls was to be sourced within a five-mile radius.

And that's where Doug Rodman enters the story. He was the man who built the Church of the Good Shepherd. Doug was a friend of my father's. The house where he lived with his wife, Peg, was on McDonald Street, overlooking the river, and my brother and I would sometimes accompany our father when he visited Doug’s house.

I was fascinated by his basement. The space smelled of old wood, Scandinavian oils, sherry-soaked cigarette smoke (Doug was a confirmed alcoholic), and the sharp iron tang of auger bits biting into timber. It was a place of tools and patience: curled wood shavings, handsaws, jack planes, sash cramps, chisels. I still have the wooden chisel mallet he gave me, and the jack plane that I used, among other jobs, when I worked as a carpenter on the restoration of the old boarding house at Rangi Ruru in Christchurch. Tools are like mementos that pass from hand to hand, their stories intertwining with those of the people who work with them. The wooden mallet Doug gave me, I used to make imitation reindeer hoofprints on our lawn every Christmas Eve, a ruse that convinced our daughters of Santa's existence for years.

Doug Rodman was an old-school craftsman, even if his reputation for drink was as firm as his grip on a square. He and his cobber, Les Loomes, had raised the walls of the church beside the lake, laying the stones by hand, mortising the joints, cutting the bird’s-mouth seats of the rafters, splitting and fitting the timber roof shingles, and installing the joinery. And in doing so, he had become part of something much larger than himself.

Lake Tekapo and the Two Thumb Range

Esther Hope, the artist who produced the conceptual drawings of the church, was born in 1885 in Woodbury, just down the street from another church, St Thomas', where my wife and I were married. Esther studied art in London at the Slade School of Fine Art and the Chelsea College of Arts. After completing her education, she spent several years perfecting her craft in Europe. She was in Brittany when World War I broke out and, upon returning to England, she worked as a truck driver and as a Voluntary Aid Detachment driver in Malta. When the war ended, Ester returned to New Zealand and married Harry Hope, the owner of Grampians.

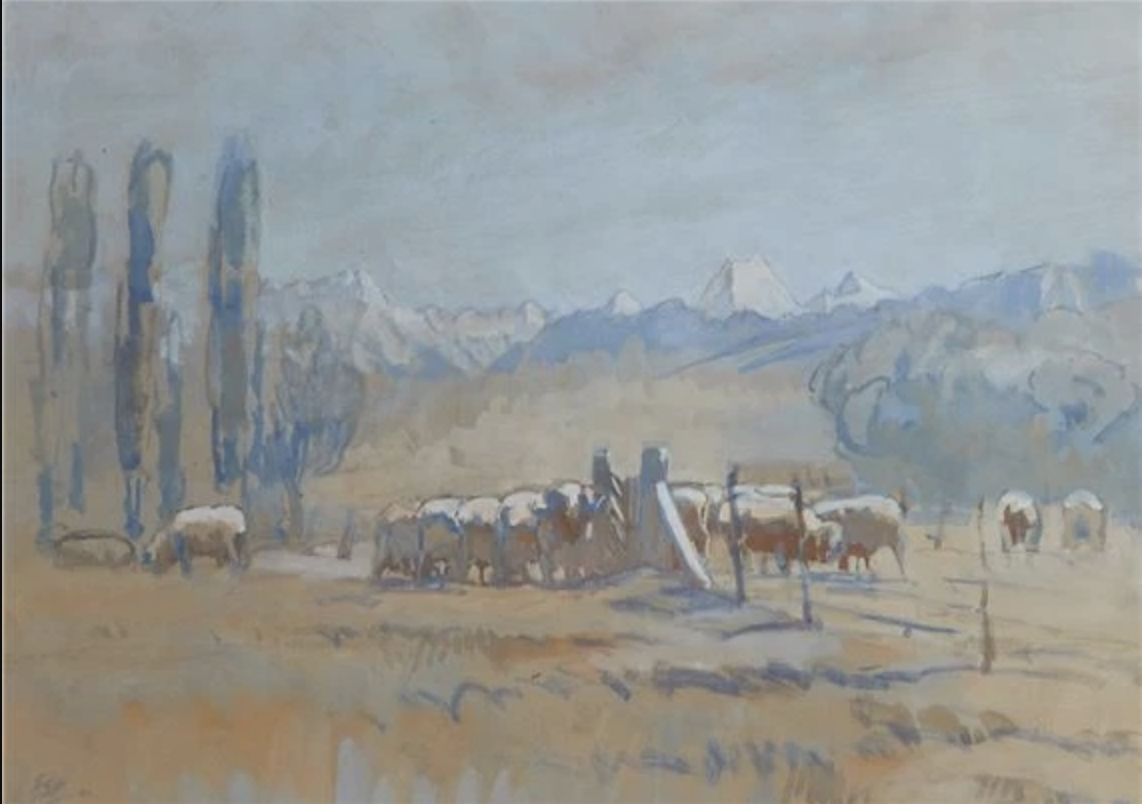

At Grampians, Esther Hope began painting the landscapes of the Mackenzie Country: the vast sky, the long views framed by pencil-thin Lombardy poplars, the sinuous curves of the willow-lined creeks on the beige background of the basin, and the distant, glacier-encrusted line barrier of the Southern Alps. These were views that I came to know intimately: on foot, on horseback, through the windscreen of my Holden ute and in the blur of a dog’s run.

The view from Grampians, Watercolour by Esther Hope.

The same view as the watercolour above, photographed by me in December 1981.

What Esther captured in watercolour, I traced in dust and sweat and stock movement. Her brush followed the contours my boots did. The light she washed onto the page was the same light I watched falling across the hills at dusk. And in both acts—hers and mine—there was the same quiet reverence for land, weather, and the long lines that stretch across memory.

Her granddaughter, Sally, is also an artist. In November 1981, she and her husband, Nigel Buxton-Hope, came to live at Grampians for the summer. Nigel worked alongside us during the lamb-marking season that year. He was from Brixton: London-born, freshly steeped in the aftermath of the Brixton Riots, more familiar with the acrid smell of exhaust and gutters than the fresh, clear air of the South Island. We called him “The Brixton Basher”, more out of affection than mockery.

At the time, none of us really understood the political landscape he’d come from. To us, he was just another pair of hands to lift lambs and another set of stories to tell. Like his wife and his wife’s grandmother, Nigel was also an artist. He’d sketch during smoko: drawing dogs, our faces, the jagged ridgelines that framed the paddocks of The Whalesback. He moved with the grace of someone used to crowds, noise and the feel of asphalt underfoot. And yet here he was, out on the flats of the Mackenzie Basin, knee-deep in lambs, the smell of blood and steel filling the air instead of the aromas of diesel smoke, uncollected garbage, and weed.

Tailing in the Mackenzie Pass, November 1981.

In July 1882, another of Sally Hope’s ancestors, Arthur Hope, married Francis Tripp, the daughter of runholder Charles Tripp, the pioneer high country farmer and owner of Orari Gorge Station. Tripp himself had married one of the daughters of Henry John Chitty Harper, the Anglican bishop of New Zealand. In the same ceremony, another of Bishop Harper’s daughters had married my great-grandfather, Charles Robert Blakiston. That meant that Sally and I shared some family connections, with her great-grandfather and my great-grandfather being brothers-in-law.

And so it was that these strange, tenuous threads—of blood and circumstance, of tools and traditions, of wood shavings and watercolour—connected us all, with the Church of the Good Shepherd standing like a spoke in a wheel of memory, faith and place.

The Church of the Good Shepherd was designed to blend with its environment. The stonework was left rough, lichen allowed to grow, and the native vegetation untouched. It wasn’t built to stand out. It was built to belong, not just to the landscape, but to the history of the shepherd. It was intended as a memorial: to commemorate the pioneers of the Mackenzie Basin. But for me, as a young shepherd, it was something more immediate. It was a waypoint. A familiar shape on the skyline as I moved sheep through that wide, weathered country. The lake glinting beside it, the mountains behind, the dogs panting, and the wind sharp with snow. That church wasn’t just a symbol. It was part of the geography of my working life.

Back then, it wasn’t locked. There were no fences or guards. You could walk in, sit quietly, listen to the creak of timber and the hum of lake wind against the walls. The view from the altar—a wide window framing the lake and the mountains—wasn’t a metaphor. It was reality. And somehow, that made it all the more sacred.

To me, the Church of the Good Shepherd is a reminder that beauty doesn’t need polish. That faith doesn’t need grandeur. And that those who work with their hands—men like Doug Rodman—shape not just buildings, but memory.

When I think of that church now, I don’t picture the tour buses or the selfie sticks. I picture the dust on Doug’s overalls. The curl of a wood shaving. The heavy thud of a plane on totara. The way that the colours of Esther Hope’s paintings bleed into each other. And the silence inside that little chapel, where the light filters through rough glass and the land seems to hold its breath.

History, you see, is not just what is written down. It is also what is carried forward in memory, in hand tools, in sketches, in names spoken at tailing pens and around kitchen tables. It is carried in buildings and in banter, in windblown introductions, in nicknames that outlive first names, in watercolour shades on linen paper, and in the quiet, instinctive way someone rolls a cigarette or sharpens a blade.

Looking back, it’s astonishing how these threads—these echoes of those who came before—interconnect with each other, however obliquely. The church by the lake, designed by a woman born in Woodbury, not far from the church where I was married. Her granddaughter's husband, fresh from the urban unrest of London, working alongside me on the station, tailing lambs in the dust and sun. And Doug Rodman, steadying a lintel under the alpine sky, unknowingly anchoring all these lives to one rough little building that still stands.

Sheep in the Mackenzie Pass, watercolour by Esther Hope.