The Cannister Bell

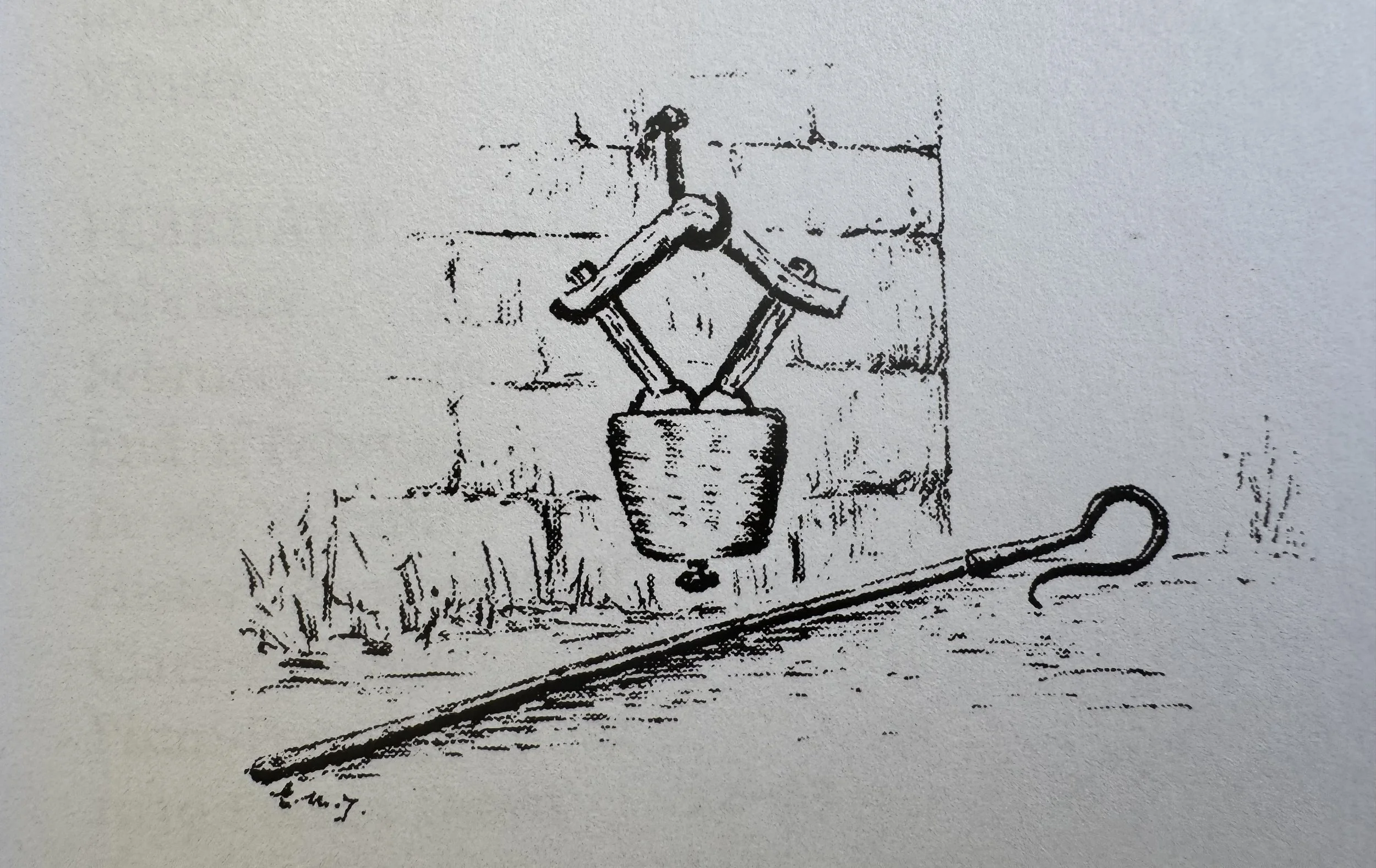

It hangs from a beam on my porch now, weathered and worn: a squat, rusted canister bell with a voice like memory. It came from Wiltshire, a gift from my aunt, Ann, Lady Blakiston, who was once a shepherdess during the war years when all the men were away. She worked the hills of Wiltshire with a crook in one hand and the weight of the land in the other, and brought with her a lifetime of stories: folk tales thick with dew, thick with the kind of truth that only oral history dares tell.

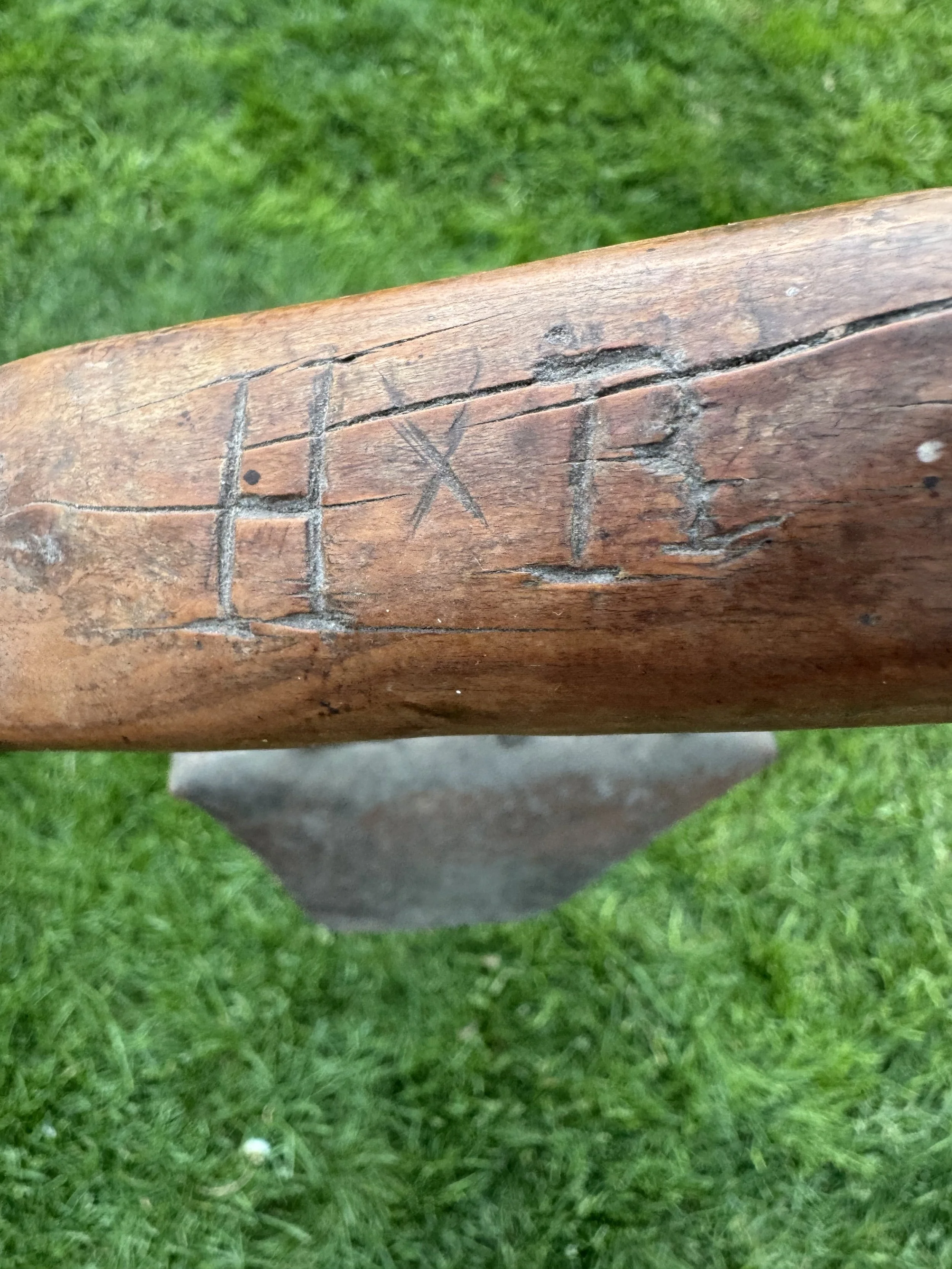

The bell itself is carved with the date 1877 and the initials HR. Whoever that was, I like to imagine he (or she) walked the chalk downs above the Wylye Valley with a few hundred Dorset ewes, and a dog that knew its business. There’s something in the heft of the bell that speaks of labour, of honest days and cold mornings, of lanolin-slick fingers and the wind off Salisbury Plain. The clapper still rings, sharp and metallic, a sound that would carry far over heather and bracken. It’s a sound that sheep come to know: half warning, half lullaby.

In Wiltshire, sheep bells weren’t just tools. They were talismans. Each flock might have just one or two—“leaders’ bells” they were called—hung around the necks of the lead ewes to help the shepherd keep track of his mob in fog, mist, or the failing light of an English dusk. In valleys where the mist pools like water and every hill looks the same, the bell was a lifeline. A way to find your sheep when sight failed and instinct took over.

There’s a Wiltshire tale my aunt used to tell about bells. She claimed that in the days before enclosure, when the land was open and the shepherds knew every blade of grass by name, bells weren’t just for sheep. They were for spirits, too. At lambing time, when the boundary between life and death seemed thinnest, bells were rung not only to locate ewes, but to ward off the “lantern men.” These ghostly figures wandered the downs with lights in their hands, luring lost shepherds to their doom.

“If you heard two bells in the night,” she said, “one was yours, and the other… wasn’t.”

She also believed each bell held a kind of memory. That you didn’t own a bell so much as inherit it. That it rang with all the places it had been and all the sheep it had followed. That’s the sort of thing you smile at when you’re young, and come to believe when you’re older.

Wiltshire itself is sheep country through and through. Before tanks rolled over Salisbury Plain, before Stonehenge was cordoned off behind ropes and placards, it was a place of flocks. Drovers moved their mobs from Devon to London, through the old drove roads of Pewsey Vale and Savernake Forest, resting at chalk-cut watering holes and weather-worn pubs. Bells would clang through village lanes at dusk, and every local could tell by the sound whether the flock was heavy with wool or lean with travel.

The bell that hangs on my porch came through that lineage. A lineage of people who knew how to move quietly, how to listen to the weather, how to count sheep not for sleep but for survival. Aunt Ann was one of those. One of the last, perhaps.

Sometimes, when the wind hits it just right, the bell rings: not loud, just a faint, metallic note in the afternoon breeze. It sounds like a summons. Or a remembering. And each time I hear it, I think of Wiltshire, of Aunt Ann’s stories, of the wartime shepherdess who wore gumboots over stockings and carried her lunch of lardy cake in a nummet bag. I think of the initials HR, carved into the bell with some pocketknife long ago. I think of flocks disappearing into fog. And the soft, certain sound of a bell leading them home.

This pencil sketch of the bell was done in 1986 by E.M. “Betty” Jeans, sister of Ann Blakiston.